Journey to the Center of the Earth Pioneers a Live-Action Stereo Workflow

For more on Journey to the Center of the Earth, see Studio Monthly‘s story on the VFX work.

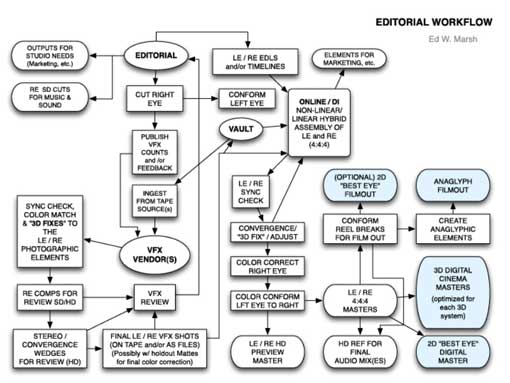

Breaking it Down: VFX Editor Ed Marsh provided this early workflow diagram to F&V. While the Journey to the Center of the Earth team was able to streamline and improve on this basic workflow, it shows the kind of extra thought that has to go into posting any 3D production. (Click to see a larger version.)

For recording a 3D image to tape with the aim of on-location playback, that posed a problem. Because one camera in the beamsplitter sees into a mirror and captures a reversed, or “flopped” left-eye image. It’s not difficult to flip the image back in post, but it’s an extra step that adds time to the process. Instead, the production used what Marsh calls a “flop mix box” from Evertz Microsystems to flop the left-eye picture and record it, in sync, to the SRW-1. “I can’t take credit for its creation, but I was one voice asking for it,” Marsh says. “I worked on two [James] Cameron documentaries where we were field-shooting on a Russian research vessel, and engineering where I was located was five decks down from where the screening room was located and it simply wasn’t practical to see the live recording in 3D while also monitoring everything else. I got very good at judging 3D by fast-toggling the [left-eye and right-eye] images and seeing what the discrepancies were. You can’t do that when one eye is flopped. I sent an incredibly simple diagram to Evertz, and they were able to modify some existing gear to give us what we needed – a box that “normalized” the eyes and kept the imagery in perfect sync that also provided a fast toggle or 50/50 DX of the images for 2D evaluation of the the 3D images.”

Dailies were played out from the SRW-1 and projected in HD. “The one frustration is that the SRW-1 was the only deck that could do it, so you had to play back your dailies from a portable deck that was just barely RS-422 controllable,” says Marsh. “To use it in post was not possible.”

Editorial worked in a 2D environment using right-eye footage only. (The right eye was significant because it was never shot through the beamsplitter, which not only flops the image, but also can introduce some softening or warpage that would need to be corrected in post.) “I spoke early on to Charlotte [Huggins, producer] and to Eric, saying, ‘OK, I’ve heard all these rules for editing 3D,'” Smith recalls. “”What do I need to worry about?’ And both of them said, ‘Nothing. Don’t worry about any of it. Cut for story.'”

It might sound a little scary to edit a 3D film in 2D, but Smith says one of the biggest confidence-boosters was the show’s ability to actually screen dailies on a daily basis. “We went back to watching rushes at lunchtime,” Smith recalls. “When was the last time you heard of a picture doing this? Eric said, ‘We have to watch rushes on a very big screen in 3D.’ That was essential. It dictated the use of certain shots that I might not have used if I had only seen them in 2D. It was great to be sitting next to my director talking about certain sequences, whether we needed the second unit to pick up shots or whatever. It’s been a while since I’ve been able to do that. On films these days, everybody gets their rushes on DVD and people don’t communicate any more. It’s a very sad state of affairs.”

To make it happen, Smith and Westervelt looked to the previs animatics created by David Dozoretz, the second-unit director and senior pre-visualization supervisor. Dozoretz re-rendered the backgrounds without characters in the foreground so they could be repurposed as background plates. “The first thing we tried to do was just split the backgrounds out a bit, putting them behind our blue-screen plates in 3D space,” Westervelt explains. “In most cases it worked. If there was something like the ocean with piranha fish in it, moving from the background to the foreground, it might be impossible to get it to work. But our foreground plates would have real 3D, and the background plates would look like a flat background, just far enough behind that they didn’t look like they were embedding into our foreground plates.”

Then you need something to capture both streams. The SRW-1 can do the job, but Journey opted instead to use a digital-cinema server, the Quvis Acuity. “That’s the best solution, because you can get it to trigger and capture the right timecode,” Westervelt says. “We would capture the two HD streams and remarry them into one 3D stereo video file that was available for playback. That’s how we built that first 3D assembly of the director’s cut.

“The only other way to do it would have been to go to an online facility, give them an EDL, and have them bring everything in and do the comps with the backgrounds. It would have been prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.”

The Acuity was an important piece of hardware in the VFX review process, too. “We started stitching together 3D assemblies fairly regularly,” says Marsh. “I got it down to a minor science using a FileMaker database and the Acuity. I made it jump through hoops it hadn’t been designed to jump through. But it worked, and it allowed us to get through our process very economically because we weren’t dependent on a bunch of other machines – DI systems that required three or four people to operate.” VFX vendors delivered QCC clips, which were dropped into the current cut of the film, married to audio, and reviewed in 3D.

How much more complicated did 3D make that process? “I’d say, on average, every shot went through at least three additional iterations just to dial in good 3D,” Marsh says. “Some vendors were better at that than others, and the ones who were better at it had taken some of our advice to heart and gotten large screening environments into their workflow. Working big reveals your errors early on. You might create something that, on a little screen, works perfectly in 3D. But then when you amplify that to the large screen, you realize just what your margin of error is. It’s micro-pixels. You might just need a tiny adjustment, but it makes all the difference in the world.”

In fact, the real problem with editorial wasn’t that it was taking place in 2D, but that it was happening in SD instead of HD. “We should have been cutting in HD. It would have made the whole post process easier,” says Westervelt.

Marsh agrees. “My one regret on Journey was that we chose to be in a standard-def metaphor for the show,” he says. “We had to go through two extra steps to see our work on a big screen in 3D. When we did the director’s cut, we conformed it in HD on a Nitris and then we brought in the other eye and basically redid all the temp visual effects work from one eye on the other eye. It was an extra step that had to be done to get us to screening. With the newer codecs from Avid and the cheaper storage, it isn’t necessary. If I were doing a 3D project now I would not do standard-def at all. In fact, I wouldn’t do any film in standard-def. We have the technology now so that HD is not a performance hit, and it gets you that much closer to reviewing your work on the big screen.”

“We do have the typical 3D trick shots, and someday we’ll all get over those,” Smith continues. “It’s very much like the train going toward the audience in the Lumià¨res’ film. You do it once or twice and everyone is very excited, but they eventually get bored with it. We did play some of those games, believe me. But on the whole, the 3D experience is about the beauty and, more to the point, it’s unbelievable how – even me as the editor – you feel like you’re there. You’re out in the mountains of Iceland, and you feel like you’re there.”

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply