While documentaries built around found footage are nothing new, it’s rare to find one made by a director who is both a cinephile and sports fan. Julien Faraut’s John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection was made from 16mm rushes of a tennis game played by McEnroe in 1984 that he discovered. Most of the film is filled with constant interruptions, including quotes from Serge Daney, the brilliant French film critic who also wrote about tennis. (It also uses an English-language voiceover from actor Mathieu Amalric.) Only in its finale does it present a straightforward vision of McEnroe, depicting him at the French Open. Faraut spent several years making the film while working at a cinematheque, and the result manages to say something about both McEnroe’s personality and the nature of tennis in a way that will resonate even with spectators who aren’t sports fans. Additionally, Faraut’s use of weathered footage in a format that’s now somewhat endangered brings up the changing nature of what cinema means in 2018.

StudioDaily: There’s been so much discourse about doping in sports that I think Jean-Luc Godard’s quote that you use as an aphorism at the beginning of your film — “Film lies, sports doesn’t” — isn’t actually true. Do you agree with it, or are you using it in a more figurative sense?

Julien Faraut: I was familiar with an interview that Jean-Luc Godard did in 2001 with a daily, L’Équipe, which is a French sports newspaper. And when I read it, I realized I was discovering a new Jean-Luc Godard. When he speaks about cinema, he oftentimes adopts a very unique persona, is barely audible and inaccessible. He actually likes that and plays with it. But when he spoke about sports, he talked in a way that was much more direct and precise on the topic of the image in sport. I used this quotation to open and close the film because I think he really understood what he was talking about. It’s a thing he was sincere in saying, but I don’t think everyone who hears it takes it at face value. My film explains what’s inherent in this quote. There’s sometimes a misunderstanding and incompatibility between reality and film, even if it’s documentary — as documentary a film as it can be. Using John McEnroe, we see someone who’s really suffering. That’s the reality of it. 30 years later, he’s still suffering from it.

You use Serge Daney’s tennis criticism as a touchstone. I know that his book on tennis is called L’amateur de tennis. I don’t know if amateur means the same thing in French and English, where it has the connotation of not having a professional background in a subject. He certainly did regarding cinema and critical theory, with respect to writers like Gilles Deleuze and Maurice Blanchot, but not sports. Do you see yourself in the same position?

I am a fan. Sometimes amateur means that. Serge Daney is a figure almost like Godard in that he’s considered to be an intellectual or, as they’re called in France, intello. It sometimes has a slightly negative connotation. People did not expect him to have this interest, in greater depth, in sports. And so I knew his texts on tennis by his reputation. I went back and read almost everything that he wrote. His interest in tennis came to him through his mother, so there was an emotional connection to the game. When he had an opportunity to write for one of the major newspapers in France, Libération, he took advantage of that. His work for them was very well-constructed, almost in the sense of a formula. A formula can be read on the surface, but Daney went a lot deeper. I like the quotation that’s in the film: “Borg placed the ball where the other player was not. McEnroe placed the ball where he would never be, ever.” I spent three years working on this film, primarily watching the rushes. McEnroe is a left-handed tennis player. He primarily uses his wrists a lot, and because of that he’s able to place the ball at angles no one had used before. It’s one reason the referees didn’t know what to do with him. I think even though Daney was writing in a style that was not uncommon for sportswriters, at a more fundamental level, he was creating a portrait of the players. There are a lot of film references. One of the important issues he deals with is duration and length of time. As a film theorist, he was also interested in the passage of time. As a filmmaker, you’re not obliged to make a film that’s an hour or 90 minutes, even though a producer might impose that kind of restriction on you. In much the same way, a player who is looking to win is trying to control its speed and acceleration so he can win the match. Daney saw this very strong connection between film and tennis in that mastery and control of the duration of time. I think he was very gifted in noting that link.

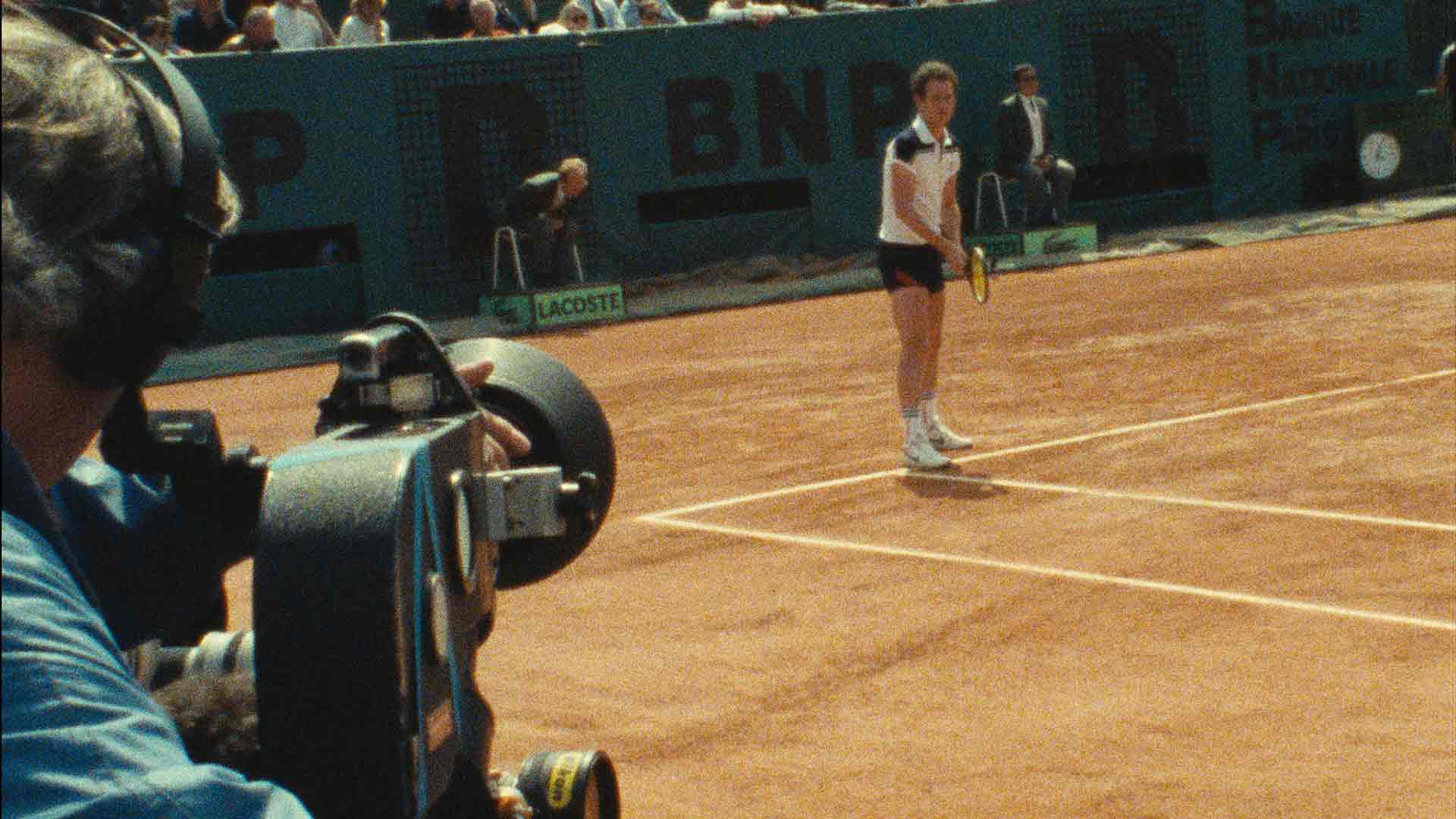

John McEnroe in John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection

Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

Now that the majority of movies are shot on video and shown on DCP, do you have a nostalgic or tactile attachment to the 16mm rushes of McEnroe you found in the archive?

I enjoyed the shock of seeing these 16mm rushes, which was the impetus for making the film in the first place. When you see McEnroe in them, it really highlights and brings to the fore the ambiguity there is between fiction and reality. This ambiguity brings us to what film is as opposed to a sports event that was broadcast on TV. Here we have an actual match that took place, but it’s seen through the prism of a very grainy 16mm image that reminds us this is also cinema. I work at a cinematheque in France, so of course I’m attached to film. I want it to be shown in a movie theater. Perhaps down the road it may be shown on TV, but that’s something for later. I really want it to be seen on a big screen.

Serge Daney wrote an essay in the early ’80s whose title translates to “Like an Old Couple, TV and Movies Have Come to Resemble Each Other.” I think that was not actually true in America at the time he wrote it, but it’s become true now. We’re in a weird period where cinephiles seem to have to claim that Twin Peaks: The Return is a film when what they really mean is that it’s a great work of art. Do you see John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection as a hybrid of TV and cinema?

It’s hard to know with Daney, because he was like Godard. He liked provocation. It’s hard to know how much he really believed and how much he was willing to push caricature at the time. I think what he spoke about, maybe slightly prematurely, in the 1980s was the death of cinema, at least as it had been known before. This period of time corresponded to a time when people felt that the death of tennis was also happening. The arrival of Ivan Lendl, who was very regimented and very interested in getting the right kind of nutrition, really represented a new kind of tennis player, the kind we see for the most time today. McEnroe was a throwback. During the match, we see him drink six Pepsis, which is not the height of nutrition. I think it was a different time, and there was a beauty to the way he played which was being surpassed by more regimented players. Now they’re interested in winning so they can get more points so they can advance higher up in the rankings. With Daney, it’s hard for us to know the exact environment when he was writing. But in the 1980s, there was a major shift in cinema. That was the arrival of video. So just the same way that people could look back at the McEnroe style of tennis as an end, people could look back at the end of cinema.

John McEnroe in John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection

Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

The found footage film has a long history. Critics have credited Ester Shub’s The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (1927) as the first feature-length documentary made entirely with found footage. What are some of your favorites and influences?

The director who actually pushed me from going from a cinephile to filmmaker was Chris Marker. In fact, my previous film was about him. He would take archival images made by others and, through his own creative process, take these images and make totally new works. So it was both him and people who were close to him, like Agnes Varda and Alain Resnais, who made that style accessible to me. The film is distributed by Oscilloscope Laboratories in the U.S., a company that was founded by Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys. The Beastie Boys were very important to me growing up in the early ’90s, particularly in the way they would use samples and mix different things. It’s the same if you see small pieces, like these rushes, and make something much bigger from them. My work is not hip-hop, but there is some influence, even on an unconscious level. If you take an example like Paul’s Boutique, which is possibly the greatest hip-hop album ever made, there are about 14 or 15 different samples interacting on each song. Here, you have the narrator’s voice, which is contemporary, mixed with the archival rushes. I credit Chris Marker with that kind of documentary, but I think perhaps I’m a hip-hop documentary maker. What I liked most about the Beastie Boys was their impromptu introduction of new elements. You might be listening to a piece of heavy rock and then comes a piece of reggae. It was this that I wanted to follow in the making of the film. We have some telescoping and interruptions. There’s the insertion of small animations.

On Paul’s Boutique, I like the way that instead of saying something themselves, they will sample another artist saying it, like reggae singer Pato Banton’s line “I do not sniff the coke, I only smoke the sinsemilla.” Speaking of music, you have an original score composed and performed by three different people, and you also use music by Sonic Youth, Mozart and Black Flag. There’s something assaultive about the use of Black Flag’s “Nervous Breakdown,” especially since by that point the film is over. The song is quite short and doesn’t even last through the entire credits. How did you select artists for the score and those particular songs?

For me, Sonic Youth is also one of my favorite groups. McEnroe is this knot of nervous energy. I wanted music to illustrate that, not just nervous energy. McEnroe can be viewed as a pure product of life in New York. Sonic Youth was very important for me. When I was cuing the slow-motion portions of the film, I chose to use a later song, “The Sprawl,” rather than one from the 1980s. I felt that was much more reflective of that kind of movement. It was important that the music create the kind of tension he embodied.

Of course, the same Mozart piece was used in Elvira Madigan. But what’s important is the anecdote the actor Tom Hulce recounts in the film that as he prepared to play Mozart, he watched McEnroe. That whole attitude and nervous energy informed his way of portraying Mozart in Amadeus. This was something important for me to make use of in the film. There’s a lot of complexity to McEnroe. Some people may have thought “He’s just an actor. There’s a performance to the way he appears on the court.” He’s a corollary to the generation who were emerging around that time, like Robert DeNiro, from the Actors Studio. Their acting was not supposed to be so obvious; you were supposed to believe that’s who they really were, not portraying a character. The fact that Tom Hulce used McEnroe as a reference point for his own performance shows how ambiguous McEnroe’s own behavior is; because of Hulce, we can look back and say “McEnroe was very theatrical, like an actor, on the court.” Another way of looking at it is to go back and see Native American art. We can say “Oh, it looks very contemporary. The design and elements are modern.” Well, in the 1940s, when that artwork was first exhibited, Jackson Pollock went to see and incorporated its influence into his own work. We’ve become used to it. When we go back to see the original that was its influence, we say “Oh, that looks like modern art,” much like Picasso and the cubists were inspired by African art. If we go back to the original, we can see something that was perhaps not there in the beginning.

To use the punk rock portion, I wanted the Ramones because they were so identified with New York and a part of that time. But when I did tests, they brought a little too much joie de vivre and lightness to the film, which I didn’t want. For that part, I had some original music composed, which I’ll talk about later. I wanted to use the Ramones in the closing credits, but I couldn’t get the rights. Black Flag’s “Nervous Breakdown” brought back the tension. It reflects exactly what happened to McEnroe. He went back to his hotel room and destroyed it. It took him some time to recover from that defeat. Using Black Flag’s “Nervous Breakdown” was both a nod to the punk rock scene and an illustration of the text.

The Ramones didn’t have the darkness I was looking for, because in effect this is like a Greek tragedy. We see in McEnroe’s body and face that he’s expressing an elemental distress, and I needed some music to highlight it. I live outside of Paris, and I thought of a group who live not far from me called Zone Libre. One of the two people who is one of their musicians, Serge Teyssot-Gay, he is possibly their biggest name and he was a musician in possibly France’s biggest rock group, Noir Désir, who have disbanded now. He has also done a lot of work at a theater where live music is played when silent films are screened. I brought him a piece of the film and he thought there might be something he could add. We initially anticipated two days in the studio and one day working on the images directly with the music. Very soon, he developed the theme you hear very often in the film, when something bad happens to McEnroe. And he does a lot of improvisation.

John McEnroe in John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection

Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection opens today at Film Forum in New York City and expands nationally beginning August 31. For a list of playdates, see the official website.

Crafts: Shooting

Sections: Creativity

Topics: Project/Case study documentary found footage sports tennis

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.