The Wall Street Journal published an interesting article last week about the ways information gathered from the habits of e-book readers is being used to generate feedback for retailers, publishers, and authors. Among the data points given up when your e-book reader phones home: How fast did you read? If you gave up on the book, how far did you get? What kind of notes did you make to yourself? And (perhaps most importantly) did you buy the sequel?

The reporter suggests that such information might be used by editors to gently guide their writers toward popular storylines that may increase their readership, or to signal when an author is badly in need of an edit. While she notes that writers and editors of literary fiction might lodge a complaint against having their work guided by such crass methodology, she also cites examples of companies that are building a business model around matching content to specific customer feedback.

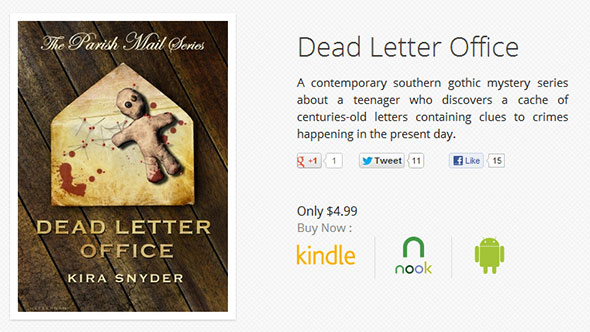

Books from the new publisher Coliloquy, for example, allow readers to control the direction of the story — much like the popular Choose Your Own Adventure books of the 1980s and 1990s. Apparently you can decide whether your YA mystery series should be more like Nancy Drew or Harry Potter, and you can pick which of several prospective dudes in a romance novel your heroine should try to hook up with. Customization options will, presumably, become richer and slicker as the technology advances.

It got me wondering whether studios have been tracking similar information about viewing habits, like keeping tabs on when viewers stop watching a Netflix title or using their cable boxes to record when they start channel-surfing or stay tuned all the way through a commercial break. Nielsen ratings and test-screening evaluation cards provide some of this information, but probably not on such a granular level. It's a tantalizing idea that could provide useful feedback for creatives. But it could also be used to suck the life out of storylines out of fear of alienating viewers.

If you polled viewers in advance, there's no way they would have approved of the penultimate plot twists in either the first or second season of Game of Thrones — and yet that program is a major hit for HBO. Like The Sopranos in its heyday, which was known for withholding the scenes of mob violence that viewers presumably craved for weeks and months at a time, Game of Thrones proves that you can confound an audience's desires and expectations and still have them coming back for more.

As any creative person who's ever been through the test-screening process can probably attest, sometimes viewer feedback is amazingly constructive, and sometimes it's incredibly frustrating. There's probably room in the market for content that's finely tuned to satisfy specific audience desires. But for ambitious, mold-breaking storytellers, easy access to feedback from smart apps that know which scenes viewers skip and which ones they watch twice could be a curse, not a blessing.

Topics: Blog Distribution and Marketing fix

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.