The Digital Cinema Society (DCS) organized a how-to event for cinematographers in New York City aimed at offering tips on making money from stock footage. Moderated by DCS President James Mathers, the panel convened August 2 at B&H Photo & Video in Manhattan, and speakers included cinematographer Mark Forman, Light Iron CEO and co-founder Michael Cioni, B&H-The Studio cameras and workflow expert Michel Suissa, and Shutterstock's director of video acquisition, Tom Spota. The topic shifted fairly quickly to encompass a free-wheeling discussion of camera technology, but here's a rundown on some of the advice about making money from your own footage library that panelists shared.

Pictured (top), from left: Michel Suissa, Mark Forman, James Mathers, Tom Spota, and Michael Cioni.

1.) Always think about rights issues. To keep your shots from being flagged by skittish network or studio legal types, don't frame them around a single entity. Instead of taking a picture of one building, compose a nice shot including three or more. Instead of shooting a single person on the street — unless you're willing to secure a model release (see below) — shoot a crowd of mostly unidentifiable people. If you really need to highlight a specific structure or person, seek permission. "If you don't get permission, even though it's legal, the lawyers will make you kill it," said cinematographer Mark Forman.

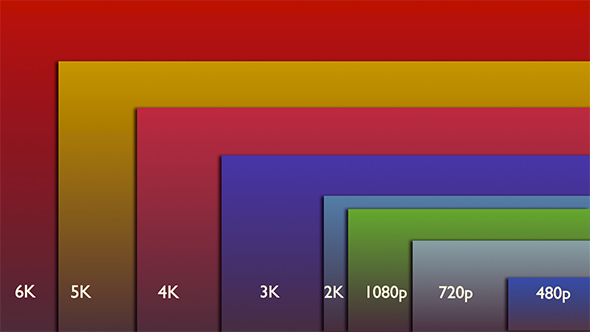

2.) Always shoot the highest quality possible — preferably 4K or better. Light Iron CEO and founder Michael Cioni showed a chart depicting the relative size of different screen formats. The image was familiar but it made a crucial point: with word last week that Red Digital Cinema's Dragon sensor was in the field, 2K resolution is decidedly closer to the right-hand (lower quality) side of the chart than it is to the left-hand (higher quality) side. There are lots of reasons to shoot in HD or 2K, but future-proofing footage and preserving its value as stock is most definitely not one of them. (B&H's Michel Suissa shot some 4K video of the event with the Sony F55 and then played the clips out on an HP Z820 workstation running Assimilate Scratch within minutes, just to show that 4K can work comfortably in the real world.)

3.) When considering subjects, look out your window. "I have a really incredible rooftop, with a view of Manhattan north and south," Forman said, explaining that TV series are always looking for establishing shots of New York City. If you're lucky, pointing a camera out your window could conceivably net you thousands of dollars worth of stock shots. Forman also remembered a cross-country shoot for an indie film, during which he specified that any shots he captured without actors in the frame (such as Monument Valley vistas) would be his to keep and license, giving him an instant archive of Americana.

4.) Think twice about shooting time-lapse for stock. Shutterstock's Tom Spota said time-lapse is a popular footage category, but Forman argued shooters should consider whether the potential revenue is worth the significant time investment required to babysit a camera for 12 hours or more. "Unless you want to do [time-lapse], it's not worth it financially," he said.

5.) Retain ownership. Don't get roped into an agreement where another entity owns your content outright. License footage to others — don't sell it to them.

6.) Balance the potential upside of microstock agencies against the traditional model. Forman doubted that the microstock model would provide big returns unless you have a sizable library of footage to monetize, noting thtat licensing a single shot to a TV series through a traditional stock partner can generate many times as much as licensing it through a site like Shutterstock. However, Spota countered by noting that there are 27 million small business owners in the U.S. who constitute a huge and potentially lucrative market because they have been forced to become content publishers on the Internet.

7.) Go the extra mile: work with a model. Spota indicated that model-release footage is among the most in-demand among Shutterstock's customers, along with imagery related to business, healthy lifestyles, and education. Just make sure you get the proper clearances, a task your agency can help you with by providing the appropriate forms and other guidance.

8.) Don't worry about 3D. Uptake for viewing stereo 3D content at home and on the Internet has been minimal, so unless you're working on assignment, it doesn't make much sense to amass a library of stereo footage. "4K is the 3D we've always wanted," Cioni quipped.

9.) Stay up-to-date with camera technology. Yes, that's easier said than done. But Cioni noted that sensor technology improves so steadily and surely that whatever camera is on the market with the newest sensor is likely to provide the nicest images. Keep your eyes and ears open for any chance you might have to shoot with the latest and greatest and hang onto some footage for your own purposes.

10.) Use LTO tape for cost-effective archiving. Cioni estimated that archiving footage to LTO tape costs about $0.04/GB, making it a bargain compared to spinning discs or archival film negatives. Until atomic-scale magnetic memory is a real thing you can plug in and use, tape is likely to be your best bet.

Topics: Blog Business Shooting stock footage

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.