How Prime Focus Put New Depth in the Picture While Honoring the Original Work

We’re off to see the Wizard — and this time, he’s in 3D. Stereo conversions have become pretty common for new studio tentpole releases, but they’re relatively rare when it comes to older films, especially studio catalog jewels like The Wizard of Oz, originally released by MGM in 1939 and now part of the classic Warner Bros. library. What’s it like to tackle a stereo conversion job involving some of the most famous images ever committed to film?

Well, Prime Focus would know. The company’s proprietary View-D 3D-conversion process was used on Star Wars: Episode 1 – The Phantom Menace, Transformers; Dark of the Moon, Shrek 3D, and more. Now, it’s been put to the test on a new 3D release of The Wizard of Oz, which premieres September 15 and begins screening September 20 exclusively in IMAX theaters. We asked Chris Del Conte, Prime Focus’s VP of business development in Los Angeles, and Justin Jones, a View-D supervisor in Vancouver, how the company met the classic conversion challenge.

“Everybody was a little apprehensive about the idea of putting our hands on such a classic film,” Del Conte told StudioDaily. He remembered that Ned Price, the VP of mastering for Warner Technical Operations, was available to provide guidance on what existed on the actual physical stages where The Wizard of Oz was shot.

For example, Price might note that, while the set for Dorothy’s room in Kansas was only 12 feet across, the depth-converted version looked bigger than that. In general, the 3D team would defer to that reality rather than transforming the environment. “If you had shot the film with a digital camera, standing on the set,” Del Conte said, “you would see what we were trying to interpret with our conversion process.”

But once the team felt they had locked down the correct natural depth for all of the scenes in the film, it gave them the confidence to start using 3D a bit more aggressively. “Once you had control, you could make better creative decisions,” said Justin Jones, View-D Supervisor in Vancouver. “For example, you could make the witch more uncomfortable to viewers when she’s on screen. Once we had her in depth, we pulled her chin and nose out more than we would have normally. It’s subtle. It’s not about the conscious perception of the viewer. We didn’t want to pull it more and make it a gimmick. We’re not trying to make a ride film. It’s about respecting the material.”

Work began the way it always does on a 3D conversion job, with stereo conversion artists isolating every object in every shot in every sequence in the film. In the meantime, the View-D team worked closely with Price at Warner Brothers, who provided a 2K version of the studio’s recent restoration of the film, as well as with VFX supervisor Mike Fink, who was brought on to oversee the stereo conversion, to develop depth scripts laying out how the depth would flow, sequence by sequence.

“A lot of the design work happens at the very beginning of the process,” Jones said. “Once the elements are isolated, we have a stage where we place everything in depth, working out the overall environment – the set, basically – and then giving everything the proper volume and sculpting. We follow a lot of basic rules in the beginning, asking ourselves, ‘If the film were shot in stereo, how would the 3D look?’ And once that is established we can get creative and alter things a little bit to help tell the story. After the depth is placed and everyone is happy with the results, the final polish is put on. The only changes at that point are convergence changes and other minor adjustments.”

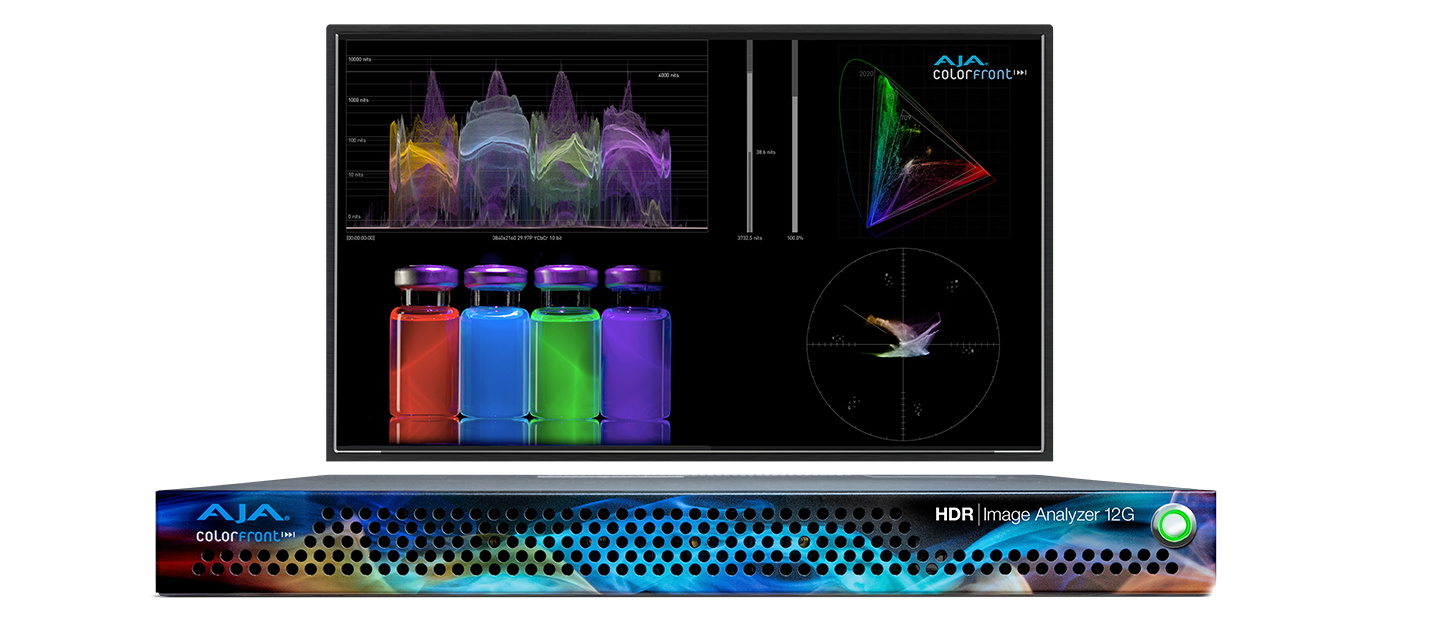

A disparity map is created that shows the frame in grayscale. Each shade represents depth, so nearer objects appear lighter, and farther objects appear darker. These shades then coordinate to values between 1 and 0 that help stereographers determine how much disparity will be between left and right eyes to create the depth effect. Images courtesy Prime Focus.

A 3D conversion is obviously a huge job, so being smart about scheduling is key. After a complete, shot by shot analysis of the film, the View-D team estimated how long each stage of the process would take based on the complexity of different scenes so that a schedule could be set. In all, the project ended up taking place on a 14-month schedule, for everything from development to final delivery, which Jones describes as “a good amount of time” for a conversion job.

It was especially helpful since work was complicated somewhat by the age of the film. Originally released in 1939, The Wizard of Oz doesn’t look much like a contemporary blockbuster. The film grain has a different quality, and the restored digital elements still exhibited some color shift and flicker that the team had to pay close attention to. But Jones said restoration is a very different task from 3D conversion. “[Warner Bros.] worked on the image before they gave it to us, and they did more work after we finished,” he said. “[Those imperfections] will be less of an issue in the final product. But while we were working on the files, the idea was to stay as close to the original [files] as possible.”

In a way, the real challenge wasn’t the film’s condition, but its style of filmmaking — specifically, the more leisurely editorial sensibility of Hollywood’s Golden Age means there are fewer edits, and viewers have more time to examine each shot. “On a film this old, the cuts are really long compared to newer films,” Jones said. “20 percent of the shots in this film were over 1000 frames long. That definitely created a challenge creatively, because viewers have more time to let their eyes go around the frame. And on a technical level, it creates data management issues as you transfer files within a location and worldwide because the shot files become heavier with so many frames and so much roto work. Think of the dancing Munchkins, with their costumes, and all the leaves on the trees, and the backgrounds of the sets. A lot of files have to be managed as one asset.”

“To give you some ballpark numbers, a 100-minute movie today is between 800 and 2,200 shots,” explained Del Conte. “Wizard was just about 650. It affected how our roto and paint teams would approach the work. We really adjusted our workflow to compensate for so many long shots.”

Among the biggest challenges on The Wizard of Oz were the shots with dancing Munchkins, which featured anywhere from 50 to 100 extras spinning around (with their limbs moving toward and away from the camera repeatedly) amongst the film’s detailed foliage and other set dressing. Accuracy was a requirement, especially in close-up sots depicting iconic characters like Dorothy and the Cowardly Lion. “We had to be very accurate with the sculpting,” Jones said. “We don’t do any automated processes. The more you automate 3D, the worse it looks. So we really put a lot of focus on character sculpting – making sure it’s accurate and that you’re getting the same detail you would if you shot it. And getting that in shots that are more than 1000 frames long, the accuracy has to go way up.”

Accuracy may be the best policy, but it’s not without its own dilemmas. What about those painted backgrounds, for instance, which only gave the illusion of depth on set? “We had to decide what to do with the painted backgrounds,” Jones said. “Do we keep those flat, or do we extend those in depth? We tried a lot of different looks, and we ended up putting some depth in the background. But we’re not trying to sell that it’s not a painted wall. It’s a really cool look.”

They also thought about the film’s famous transition from monochrome to color, wondering if it would be appropriate to keep the Kansas sequences flat, only opening up the stereo depth for the section of the film set in Oz. It didn’t work, in part because the film’s opening scenes just took up too much time. So the View-D team simply employed the stereo effects more subtly in the black-and-white segments. “As soon as we open the door [into Oz], it’s pretty much the maximum amount of stereo,” Jones said. “She steps into a big world. It’s not going from completely flat to stereo, but it’s the same effect the filmmakers were originally going for.”

As far as takeaways from the project, Jones and Del Conte both called it a lesson in how good the results of stereo conversion can be when the artists involved have the time to plan and execute it properly. “When Warner Bros. released Clash of the Titans, it was the first full-length conversion,” he said. “Designing the depth and trying out new looks for The Wizard of Oz, we spent about 10 weeks on that alone. That’s about the same amount of time we spent on the entire Clash of the Titans project. If you put more time into the design of the film, you’ll get a better product. That’s something we’ve seen clients start to appreciate more. It allows you to make decisions that support the story instead of just taking something in 2D and making it 3D.”

“We at Prime Focus knew that this show, a nostalgic library title, had to be our best quality work and something to be proud of,” Del Conte said. “Going into the theater and seeing this film in 3D, whether it’s your first time or your 50th time with The Wizard of Oz, it’s going to be a new experience. And in IMAX? It’s great. This is a chance for people to enter the world of Oz in a way that’s never happened before.”

Crafts: Post/Finishing

Sections: Technology

Topics: Project/Case study 3d conversion Prime Focus the wizard of oz view-d Warner Bros.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.