Beginning His Career, Mentoring Young Sound Artists, and Collaboration with Directors

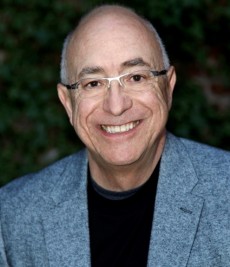

Next month, the Motion Picture Sound Editors will present Randy Thom with its Career Achievement Award at the organization’s annual Golden Reel Awards ceremony. The honor recognizes an artistic career spanning more than three decades, more than 100 films and two Academy Awards (for The Incredibles and The Right Stuff). Thom, who began his career in radio, serves as director of sound design at Skywalker Sound, where he has worked since the mid-80s. One of the most influential sound artists of his generation, Thom has in recent years become a vocal proponent of the importance of sound as a storytelling tool in film.

Thom shared his thoughts on winning the MPSE’s Career Achievement Award, his career path and the state of film sound today.

What does it mean to you to be recognized with the MPSE’s Career Achievement Award?

It is a huge honor. It comes from people who understand what I do and know what the work entails.

What originally interested you in pursuing a career in movie sound?

In the early ‘70s, my girlfriend worked at the Pacific Film Archive at the University of California, Berkeley. It was an art house theater that played all kinds of wonderful movies and occasionally she was called upon to take filmmakers out to dinner. I tagged along for some of those things and that gave me my first glimpse into the lives of filmmakers. I met a few people whom I would later work with, David Lynch being one and Errol Morris being another. Before that, it was like Alice through the Looking Glass. I didn’t know how one would begin to work in the movie industry, but meeting those people made it seem possible.

I had always been a movie fan, so starting in 1975 I began in earnest to try to break into movies. I had been working in radio before that, doing various kinds of sound work, producing pieces for National Public Radio, working on radio plays. I knew how the equipment worked and was growing more interested in using sound for storytelling. So I started knocking on doors, but I didn’t have much luck for a long time. Then, a friend suggested I call Walter Murch. The friend had taken a class from him at the San Francisco Art Institute and said he was a nice guy. I called him and he invited me to sit with him and a group of other people who were mixing American Graffiti into stereo. I sat there all day and at the end of the day, he asked me to write an essay on what I’d seen. I talked about the workflow and how the people interacted. He liked what I wrote and miraculously hired me to work on Apocalypse Now.

That was quite an opportunity.

It was incredibly exciting. We knew it was going to be an important film. There was a lot of buzz about it. I’d paid my dues in public radio, but to be hired on that film was an incredible stroke of luck.

Do you have an opportunity now to mentor young sound artists?

I do. I always have an intern and I’m around lots of other young, aspiring film sound people. It’s a way to give back a little, and it energizes me. Young people come up with new ideas and ask good questions. It’s one of the things that helps me from becoming jaded.

Another thing that keeps me energized is Skywalker Sound’s partnership with the Sundance Institute. We help young writer/directors develop their projects. We get involved very early and offer advice about their scripts. My soapbox for the past 20 years has been to point out that it is wrong to think of sound design as a kind of decoration that is added to the film at the end. Sound ideas should influence the script. Our collaboration with Sundance is a perfect avenue to promote that idea.

What advice do you have for young sound professionals?

Be persistent. If you are persistent, a fun person to work with and reasonably smart, you have as good a chance as anyone. Persistence is the important part. Even after you make it through the “looking glass” and get your first job, you still have to get the next job. You have to continue to be persistent, even when you are as far along in your career as I am.

You have worked with a lot of talented directors who employ very different styles of storytelling, but are there any commonalities in the way that good directors use sound?

Very often, directors who come from visual arts backgrounds are great in terms of sound. It must be a similar part of the brain that is operating. David Lynch is a great example. They automatically think of sound as an equal tool to picture in storytelling. They don’t depend solely on dialogue to tell the audience what is going on. They take the risk of being more cinematic, as well as more “soni-matic,” if you will, using sound to give the audience a sense of who characters are and the world that they live in.

You’ve been at Skywalker for a long time, what’s kept you there?

I’ve been at Skywalker since before it was Skywalker. It was originally called Sprocket Systems. I got involved during The Empire Strikes Back. It’s a wonderful place to work. It is very collegial, noncompetitive. No one has any “trade secrets” that they are afraid to tell their colleagues. The attitude is the more everyone knows, the better off we all are. I love that about this workplace and it certainly doesn’t hurt that it’s in a beautiful location in Northern California.

Does it benefit from being a bit removed from Hollywood?

It’s a benefit in some ways. As a practical matter, we can make audio recordings outdoors without hearing freeway noise or a lot of planes flying over. It also benefits in a philosophical way from being farther away from the people counting box office receipts.

What keeps you interested in your work?

It’s the fun of discovering new things every day. At this point in my career, producers are tempted to hire me because they think I already know exactly how to do whatever it is they want me to do. Ironically, that is rarely the case. I have to figure out a new how to do each project, because each project is different. So you’re bound to discover things.

Sound technology has changed a lot over the course of your career. Have new tools improved the creative process?

Not always. Having almost immediate access to any sound you want is not an unmitigated benefit. When you have to walk down a hallway to find something, you have an opportunity to come up with an idea that you might not have come up with otherwise. I sometimes build those delays into my working process. I get up and walk around the building. When I return to my workstation, I might have a fresh idea that I might not have had had I sat there staring at the screen. That said, you can do a lot more work a lot faster with fewer people with today’s technology. I think that is especially beneficial for smaller budgeted films. Now you can do a quality soundtrack on a pretty small budget.

Does sound get the recognition it deserves?

It’s moving to a good place. The term sound design was controversial when it was first introduced, but it’s more accepted now. There is an analogy in the visual arts. The term “production designer” was first introduced on Gone with the Wind. William Cameron Menzies was the first person to get that production credit. At the time, a lot of art directors thought it was self-aggrandizing. It took several decades for that controversy to die down. We’re now a couple of decades into “sound design” and I’m happy to see it become more accepted.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a film called Rio II. It’s a sequel to a film that came out a couple of years ago directed by Carlos Saldanha about some birds in Brazil. It’s a cute, fun movie. I’ll also be doing the sound for Guillermo del Toro’s next movie, Haunted Peak.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.