The U.S. Library of Congress Has Reportedly Acquired the Long-in-Dispute Camera Negative

Film buffs agree—Jerry Lewis's 1972 Holocaust film The Day the Clown Cried may be the worst film ever made. That's a qualified "may be," though, since nobody has actually seen the film. That's why it fascinates, all these years later—its reputation for terribleness, coupled with the idea that it will never see the light of day.

But now, buried deep within a routine film festival report in the Los Angeles Times, there is word that the film still exists, and that its camera negative is in good hands. It is, apparently, at the Library of Congress, which has agreed not to screen it "for at least 10 years." Does that mean we'll finally see it in 2025? Who knows? But it's by far the most encouraging sign to date that this weird little piece of film history may finally hit a movie screen.

With most of these kinds of things, you find that the anticipation, or the concept, is better than the thing itself. But seeing this film was really awe-inspiring, in that you are rarely in the presence of a perfect object. This was a perfect object. This movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is. "Oh My God!" — that's all you can say.

— Harry Shearer, quoted in Spy magazine's still-definitive 1992 piece on the film

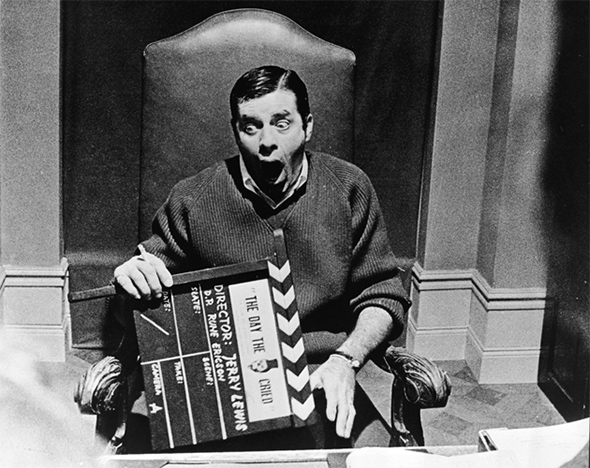

What's the big deal with The Day the Clown Cried? As the title may clue you in, it's not the kind of lightweight romp that Lewis was known for. Conceived by Joan O'Brien (a publicist who had worked for Ronald Reagan, Elvis Presley, and Mario Lanza) and co-screenwriter with Los Angeles TV critic Charles Denton, the script was rewritten by Lewis to make the lead character more sympathetic (and more of an alter-ego for Lewis himself). That might have been a bad idea, given that the story is about Helmut, a German circus clown (played by Lewis) who, imprisoned by the Nazis after mocking Hitler, is employed to entertain Jewish children on their way to the gas chambers.

If you're having a hard time believing that such a film was scripted, let alone shot, you can actually read the script online.

It was a rough shoot, with money drying up partway through and Lewis financing it out of his own pockets. The project's legal status was murky. There was no money to finish the film after the shoot. The screenwriters, unhappy with Lewis's changes to the script, reportedly blocked the film's release, saying Lewis's option on the material had expired before production began. The film has only been seen by a precious few insiders as a rough cut, though Lewis himself has expressed interest, in rare comments on the matter, in finally allowing the film to be shown in some form.

It's unclear what may have transpired behind the scenes to free up the original negative, which was said to have been kept in Stockholm for decades as security by a company still owed money on the film. Jerry Lewis is 89 years old now; perhaps he figures that in another 10 years he'll either be gone from this world or simply beyond caring what anyone thinks of his most controversial film. Either way, the prospect is tantalizing for movie buffs. Who can resist being able to finally, after more than 40 years of pure speculation, have an informed opinion about one of the most notorious films ever made?

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Leave a Reply