Editorial Services VP Jay Tilin & Colorist Martin Zeichner on Doing Research, Making Metadata, and Setting DPs at Ease

Earlier this fall, Netflix summoned an array of technology journalists to New York to teach them about high dynamic range (HDR) technology, using the OTT operator's range of Marvel superhero shows as a guide. The still-forthcoming Iron Fist is Netflix's first Dolby Vision original show — that is, cinematographer Manuel Billeter is conceiving it for HDR from square one, rather than having it regraded after the SDR version has already been completed. But the case study for post-production was Daredevil, which was regraded for HDR by colorist Tony D'Amore at Deluxe's L.A. facility. With reporters assembled in a grading suite at Deluxe in New York, D'Amore called in via telephone and oversaw a remote-grading session, controlling the New York office's Da Vinci Resolve software from the other coast and explaining the Dolby Vision process.

(Deluxe's claim to HDR fame? The company has worked on more than 100 HDR titles — including, in its New York office, season 2 of Netflix's Marco Polo, which it says was the first-ever Dolby Vision show.)

D'Amore described Dolby's crucial "content mapping" software, which analyzes the image to create metadata that will allow the image to appear correctly on playback, with brightness levels re-mapped to match the specific capabilities of any Dolby Vision-equipped display. The standard display used by Deluxe for HDR grading is the Dolby Pulsar monitor, which is a 4,000-nit display that far outstrips consumer monitor capabilities. (One nit = 1 candela per square meter.) Even so, it doesn't come close to maxing out the HDR spec, which supports up to 10,000 nits. For comparison's sake, Deluxe colorist Martin Zeichner said the Rec. 709 spec allows for 100 nits of peak brightness, while laser projectors in a theatrical setting can reach up to about 1,600 nits. The trick is generating metadata that will allow the image to be generated correctly under a range of varying viewing conditions.

"We're protected for the future — just in case somebody does one day have a 4,000 nit TV, we're grading all the way up to it," D'Amore noted. "Even if you have a 600 nit TV, the mapping pushes the limits of the set you're watching on…. For the most part, anything above 500 nits is going to be really impressive."

How bright is too bright? Specular highlights on the Pulsar monitor were sometimes quite literally dazzling, making it difficult to focus on the very bright screen in the dark room. In response to a question from StudioDaily about the possible emergence of best practices for limiting brightness levels, D'Amore said HDR simply takes some getting used to. "Every DP I've worked with so far on any of these shows I've done in HDR has said the same thing," he admitted. "The usual first reaction is, 'I don't like it. It's too bright. It's blinding me.' But what you notice is, the more you watch it, your eyes adjust to it…. It makes it true to life."

StudioDaily stuck around after the demo for an extended conversation with Zeichner and Jay Tilin, VP of Editorial Services for Deluxe and Company 3 in New York, about Deluxe's experiences implementing its HDR workflow. An edited transcript follows.

Colorist Martin Zeichner sits at the control panel at Deluxe's New York facility.

Jay Tilin, VP of Editorial Services for Deluxe and Company 3 in New York

StudioDaily: I'm thinking about two different questions. One is, for the colorist and the facility, how much does this complicate workflow in terms of color management — making sure you're in the right color space and calibrated to work in HDR properly? And then on the other hand, when you bring in DPs in who are unfamiliar with this technology, what do you do to make them comfortable and keep them creatively on point?

Jay Tilin: They're related questions.

StudioDaily: Where should we start to address them?

JT: How about the beginning?

Martin Zeichner: The beginning, for us, was February of 2015. We had done the first season of Marco Polo in 2014 and we were gearing up to do the second season. Dolby knew that Netflix wanted the second season of Marco Polo to be graded for high dynamic range. So they invited us and a few other people to their office in midtown Manhattan to view the Pulsar monitor and a Maui monitor. To see what we were getting into.

JT: That was our introduction. Ta-dah! Here is HDR. This is it what it can do, this is it what it can be.

MZ: They had an episode of Marco Polo from the first season that had been regraded to HDR in California. I was very familiar with the SDR, but it was an exciting surprise for me to see what it could be [in HDR]. They also had a trailer from the first season that had been regraded for HDR. And they also had some other content so that we could get a feel for this. From that, we were left to do our own research, consulting with Dolby engineers along the way. We had a lot of discussions between ourselves and the producers of Marco Polo, the Weinstein Company, and also the directors of photography …

JT: And Netflix.

MZ: And Netflix. And we had a lot of questions, as you can imagine. We came up with ways of either solving those problems ourselves or knowing what questions to ask the Dolby engineers.

JT: That was our introduction to the process. We talked about what the endgame was, what we wanted to achieve, and then set out to do our research. We went back and learned all about what the cameras are capable of, what bit rate would mean to the process, what resolution would mean to the process, what the monitoring environment would mean to the process, and basically educated ourself as deeply as possible in terms of what the process would entail before we even got our hands on the tools with which we could start creating the images.

MZ: And this was even well before shooting began on the second season.

JT: Before production ever started. Aa lot of this, I believe, was because we wanted to lessen the impact for the DPs and the directors in terms of the complicated nature of what it could be. We learned about the LUTs and the PQ color space and how we were going to get from what the camera shoots into these color spaces. We involved our image science and our color science teams at Efilm — and the Marco Polo production had already decided they were going to shoot with basically the perfect camera for high dynamic range, the Sony F55, which is a full 16-bit camera. They were already shooting raw. They had already, in effect, done [HDR production] in season 1. So we went to all of the vendors and all of the manufacturers and researched and got as much information as we could, not only so that we could understand it, but to simplify it for the creatives as much as possible. We didn't want to burden the DP if he didn't need it or want it. He wants to know what his image is going to look like. We worried about the technical details.

MZ: We want to take the technical details as our starting point and use that to solve aesthetic problems and present it to the directors of photography and the executive producers who are not necessarily versed in the same things we are. There were three directors of photography — one of them was in South Africa so I never met him face to face, but the other two would work with me like five days on each episode — and what I found was that, as time went on, they were more and more willing to exploit HDR. At first they were rather conservative about it, and later on they became more exploitive of it. Which was something that Dolby wanted to see. They wanted Marco Polo to be their showcase for HDR.

SD: Right. And it's interesting because it's not just that the DPs haven't seen something like this on a TV monitor.

MZ: Right.

SD: They also haven't seen it in a theater. Whatever the camera is able to capture in terms of dynamic range, we simply have not …

JT: We haven't taken advantage of it. That's an important point. Modern digital cameras are capable of capturing essentially the content that you can use to create HDR.

MZ: Even if the images are not visualized for it.

JT: The data is there. The cameras are capturing that bit depth.

MZ: You could even say that reality is high dynamic range …

JT: [Laughs]

MZ: … and what we've been seeing up until now is just a pale shadow of that.

SD: Because of the color space.

MZ: Because we're limited by our displays. Now the displays are offering more, we can present more.

SD: Has Resolve been your HDR environment exclusively?

MZ: I have also worked in HDR with Baselight. The one other color platform that I am familiar with — but I have not seen their HDR tools personally — is Autodesk Lustre.

JT: I think here in New York it's primarily been Resolve, but overall its been Resolve and Baselight.

SD: So is it as simple as telling Resolve, "OK, now we're working in Dolby Vision?"

JT: [Laughs]

MZ: Would that it were that simple. I think the color science and engineers have made their mark in building a foundation for Resolve and Baselight for HDR as a different kind of practice, and it is up to the colorists to take the ball and continue. It is not a simple process. It is a process that is still in development.

SD: But it has to look simple for the client because you're abstracting all of that …

JT: Yes. That was our goal.

MZ: It takes a lot of work to make it look that simple.

SD: … and just giving them the images that are true to what's going to be delivered.

MZ: So that they can say, "Oh I don't like this. What can you do with that?" And I can say, "I can do this, I can do …" like a virtuoso.

JT: You also asked about how it works from a facility standpoint and from a business standpoint. Dolby has done an incredible job of coming up with the science to make this as user-friendly as possible. But then we got to the post-production business end of it. And as we worked through that with Dolby, we did find there was a part of the business end of it that they actually didn't understand. When you sit in the room with the colorist and the DP and you grade and you create beautiful images, that is certainly the primary goal, but that's only the very first step.

MZ: To Dolby's credit, they were very willing to learn. They were very accepting of suggestions that we made. Dolby's deep background has always been sound, and they had to change direction a great deal. They had to hire color scientists and video engineers to thrash this whole process out, and they did an incredible job.

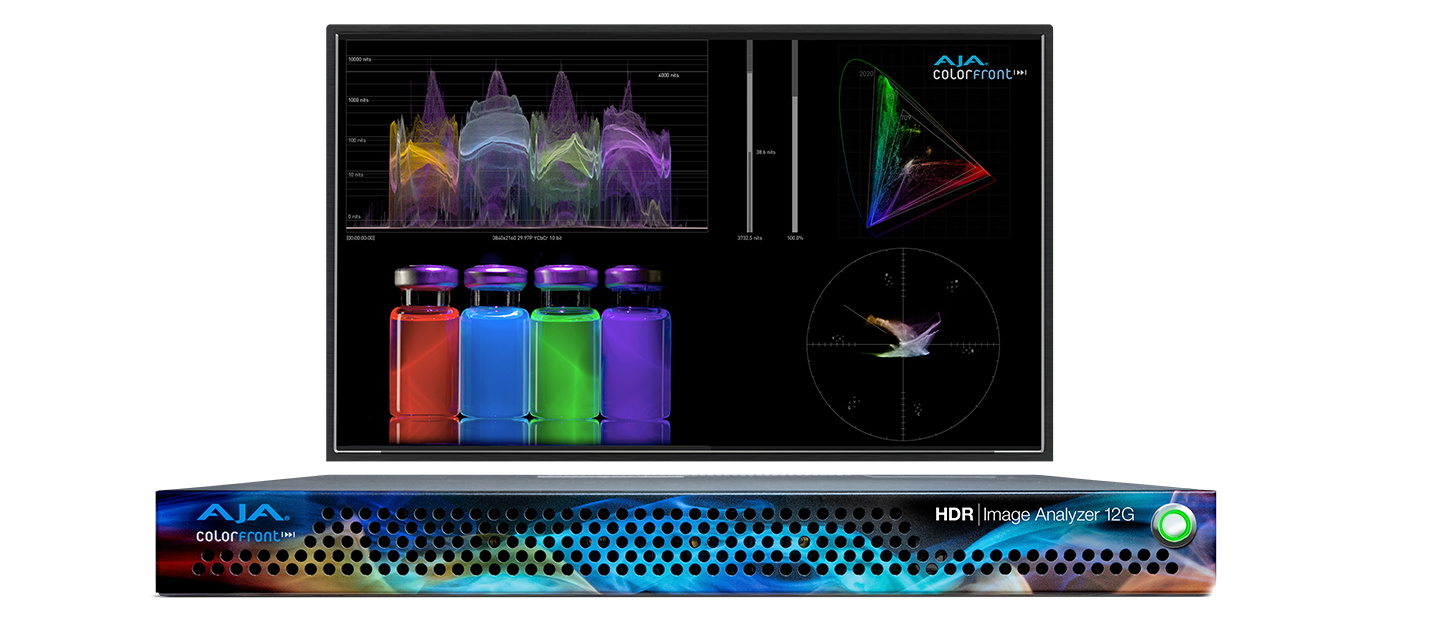

JT: They've already come up with the technology and we had to figure out a way to implement it — what Tony was talking about, this content mapping unit (CMU). You don't see it here. It's a black box that lives in the back somewhere with Dolby software on it. They gave us the software, and we had to build hardware around it to accommodate it and figure out how to implement it in the room. And different wave format monitors. How does Martin look at the signal and judge what he is working on?

MZ: As it turned out, there were actually two CMUs, and Dolby was a little surprised that we were asking for the other one. We have an online CMU, which would play down the images in real time, getting metadata from the color platform, but its output is only capable of doing 1920×1080. There is another CMU that they call the offline CMU, or the CMO, which is resolution-independent, but it doesn't operate in real time. So you can get a Rec. 709 4K render from an HDR PQ render with metadata, but it doesn't run at real time. They did not originally visualize that that would be of any use to a facility like us. And the fact of the matter is, people will ask for a QuickTime of the show to show to their executive producers. They can't watch an HDR version of it. They have to watch a Rec. 709 or an sRGB version.

JT: We also have to do quality control of the content that we're putting out, which they had not anticipated until we had this conversation. In addition to the visual media we create, there's a metadata file, an XML file, that has information about the entire show, and that's what this mapping is.

MZ: The idea is if you have an HDR render, which takes up like 4.5 TB for a one-hour show, and the XML file, the XML file is a few meg, you can derive from the combination, with the proper software, anything else you want.

JT: But there's nothing even commercially available that will actually read this file and the metadata file to be able to even quality-check the metadata to make sure the Resolve, for instance, is creating it correctly. We did find flaws in the software process, but it was only through being able to get this additional software and going through that process. Dolby was great about it but they said, "Huh, we never thought about that. You're right. We do need to do that."

MZ: And there were other issues, like titling. What level should the titles be at? How do you deal with the titling if you don't have more than one Pulsar monitor? The titling is done in a separate room altogether. When we first started this, SMPTE had not yet standardized the gamma curve for Rec. 709. It was only very recently that the Rec. 1884 came out that standardized the gamma curve of Rec. 709. And then there's the issue of visual effects. VFX has adopted, within the past five years or so, a completely different color space called scene linear, and that proved to be very useful to us. So I'm seeing the two different worlds, VFX production and color correction, starting to share information, knowledge and technologies.

SD: Does VFX deliver flat shots to you that you then grade?

MZ: My understanding is that VFX delivers to us an image that, using LUTs to do their transforms, matches the original plates that I have in my timeline, so that when I color the plates in the timeline, that color can be used for whatever they do in VFX. And then they will supply me with mattes or anything else that I might need to color the composites.

JT: A standard process — and this really does not have anything to do with HDR except that it complicates it a little bit — is that in addition to creating the full-res content in the original color space, VFX would also deliver back to us a proxy file for approvals that gets cut into the sequence, and they usually want that to match dailies color. So we provide them with the LUTs and CDL values that were captured during the dailies process so that they can recreate that for dailies. You would not be getting HDR dailies at this point yet. That's a standard VFX workflow that we use quite frequently in episodic and feature film work.

MZ: What I find interesting is that people tend to forget how much work went into establishing that workflow and think, "Oh, you should just be able to use that same workflow." It doesn't quite work. There are other details that can bite you. We have the experience of encountering them.

JT: There's another aspect that we should not overlook here. We are working in high-bit-depth — 12- or 16-bit files — and the SMPTE standard for HDR, Rec. 2020, calls for 4K. Now, it doesn't necessarily need to be, but my prediction is there will be no HDR content that is not 4K. When you're talking about a television series, if you're talking about eight hours of content, you have sources, you have renders, you have all of these various things at approximately 4 TB per content hour. This builds up rather quickly. There were infrastructure improvements that we needed to make. Our SAN is approaching multiple petabytes at this point to be able to accommodate all these multiple shows that need to stay online. I don't want to emphasize that, but it's an important part of the process for a post-production facility business. All of our competitors and partners are facing the same thing. Where do we do these infrastructure upgrades and how do we accommodate this?

StudioDaily: The additional overhead of HDR is not as much as the additional overhead of UHD/4K, is it?

JT: Only in terms of bit depth. The increase from UHD being 10-bit and HDR being 12- or 16-bit, I believe it's about a 50% increase in the actual data size. It's half again as large.

SD: It's not nothin'.

JT: Good way to put it.

SD: I'm sure that these things continue to evolve over time, but if the point on one end of the timeline is you beginning work on season 2 Marco Polo, and the other point is, "OK, we've got this all figured out and all the bugs are out of it," how far along do you feel like you are? How close to HDR nirvana are you as a facility at this point?

MZ: We can probably deal with anything any client wants to throw at us, and any requirement that any client might have for us, but I feel like there's always more to understand.

JT: This is immature technology. No matter how far down that timeline we believe we are, it is always being extended because technology continues to emerge and there's more research and learning involved. At the point we were when we finished Marco Polo season 2, where the technology was, I think Martin and I were pretty confident that we had it. We knew it. We got it. Now we just embarked on another project recently and it threw us some curveballs. All right. Let's sit down and work the problem and figure that out. I don't believe we're the end-game experts, but we're I think pretty far down the field.

MZ: That probably won't happen until HDR is obsolete.

SD: Right. When you're learning the next …

JT: And I can't even guess what the name of that will be.

MZ: And we're in a retirement home.

SD: As you said, this is a 4,000-nit screen and the spec goes to 10,000.

JT: Correct. That's going to change the game entirely.

MZ: And the standards haven't been set. There's this schism between what Dolby wants to do with Dolby Vision and what other companies want to do with their flavors of HDR, with HDR10 and HLG [Hybrid Log-Gamma, developed by the BBC and NHK]. I have some thoughts about how that's going to all shake out, but we don't really know yet what the final standards are going to be. And that's a big concern of ours. Once those standards have been set, that may mean a whole new set of things to learn and technical problems to solve.

SD: It does remind me of something I mentioned earlier. When I've seen tech demos with DPs they've had a lot of questions. Maybe they're looking at Sony's line of TV sets and, "OK, this is our HDR set, and over here is our special-sauce set that has an even wider range so the colors are a little more saturated and a little brighter." And now the DP is confused.

JT: "What do I do?"

SD: "Because I don't know what I'm expecting the user to be looking at." When you talk to DPs and work with them, is that a widely shared sense?

MZ: DPs are caught in the middle of this. They are having pressure from the vendors, and pressure from the producers who are bowing to the demands of streamers like Netflix wanting to stream HDR content. They are also feeling pressure from the camera manufacturers to learn about what the new cameras can do, to buy new cameras and to be able to operate new cameras that they rent. I think you'll find that DPs run a gamut of their own. Some of them are very excited about the new technology and some are very conservative about it. Colorists also run the gamut between the ones who say, "I don't like it" and the ones who go for it like gangbusters.

JT: In terms of the DP confusion, I think that Dolby worked very hard to address that. This is one of the advantages of Dolby Vision. One of the primary end-user features of the Dolby process is that they will profile each consumer display that gets a Dolby Vision chip and, based on the metadata that we create in this room, it will be mapped correctly, given the limitations or advantages of that display. The DP and the colorist's vision will be carried through to that display so that there will be, in turn, less confusion.

MZ: As far as the DP is concerned, that's yet another variable that has to be proven out.

JT: It's trust.

MZ: But I will say that as time goes on, a lot of progress has been made. I remember the days of analog broadcast standard-def television, and the variance between monitors was tremendous compared to today.

SD: I visited The Criterion Collection back in the early DVD days, and they had a nice Sony XBR monitor that they looked at everything on, and they had, like, a Zenith cabinet TV from the 1970s. And they looked at their DVDs on the one, but they also wanted to see them on the other.

JT: It was the same thing with audio mixing. You'd go into a mixing studio and you had beautiful speakers, and then there was a little car speaker sitting there as well.

MZ: A transistor radio!

JT: So they could hear what it was going to sound like when it all came out of this [tiny speaker].

SD: But that's an important point, to remind the DP that it's not a dumb process. The TV is not just being given something that wasn't made for it.

JT: Yeah, and it's yet to be played out between Dolby and, let's say, HDR10, which is not dynamic mapping.

MZ: Dolby introduced the idea of a scene-referred color space as opposed to a display-referred color space, and that's essential to this discussion because the scene is what's important, not the display. You profile the display, and make the scene look right.

JT: They also are evolving, and Dolby doesn't reveal everything to me. Who knows what they still have up their sleeve?

Crafts: Post/Finishing

Sections: Technology

Topics: Q&A dolby vision hdr jay tilin martin zeichner Netflix tony d'amore

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.

Sony and Samsung don’t appear to be supporting Dolby Vision. And I’m sure there are others who don’t want a proprietary system that they have to pay for. That’s a huge number of sets. I hope the “format war” is ended by studios and services supporting both standards by default. Meaning whenever you see “HDR” it will always equal both Dolby Vision AND HDR10.

Although note that LG does support Dolby Vision with their current high-end 4K models.