In Uganda a few years ago, I was asked to shoot several scenes inside a dark apartment inconveniently located on the upper floor of a building in central Kampala. Capturing the show’s daylight exteriors was tough enough. I could manage the intense equatorial sun with a few bounce cards and improvised diffusion like old bed sheets, and by shifting some of the action to earlier or later in the day. But without a single working light kit or professional instrument, the dark interior sets posed a major challenge — the kitchen and bedroom were located in the deepest recesses of the structure, away from any windows or sources of natural light.

The reality of the situation was woefully apparent: I had too much light outside, where I definitely didn’t need it, and too little light inside, where I desperately did need it. I was thus forced to consider what I did have — two abundant resources: many young East Africans eager to help, and mirrors, in Kampala. Lots of mirrors. There was a factory just outside the city.

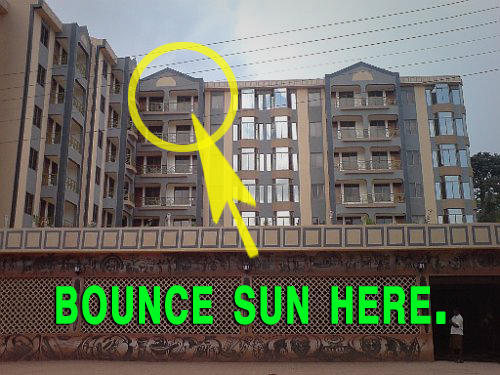

So that became the solution. Mirrors, supported by multiple two-person teams, delivered the sun from the parking lot into the upper windows of the building, down a dark corridor and into a bedroom, where the last team with a gold reflector filled the space with a magical glow. After all the shenanigans, the bounced sunlight was still too intense, so I added some diffusion through a 4 x 4 frame and the scene looked gorgeous! It couldn’t have been lit better with a 20-ton grip truck, a seasoned Hollywood crew, and a spate of pricey HMI lighting.

On sets large and small, regardless of budget or genre, the ability to work effectively with passive lighting is crucial to a shooter’s success. To light a dark interior set, this mirror crew in Uganda …

This windowless interior, illuminated by mirrored sunlight, is from the Ugandan short film “Sins of the Parents” (2008), directed by Judith Lucy Adong.

The truth is, you don’t need much — perhaps not even a single instrument — to light a scene well. Lighting manufacturers may not appreciate the insight, but the right complement of mirrors and reflectors can often work just as well (or better) for you. The use of passive lighting epitomizes simplicity. The low cost and increased speed are attractive, allowing the director and actors to work more comfortably, which, in turn speeds up the production, increases our value, and ultimately keeps us working. The adage “less gear = more work” applies. The increased use of reflectors, as opposed to active lighting, lends itself to a very smooth and speedy workflow.

The Eyes Have It: Putting the Light Where You Need It

Regardless of genre, shooters know that the lighting of our subject’s eyes is critical. A simple reflector can illuminate the eye sockets and place the desired amount of light (i.e. humanity) in the subject’s pupils. Today, the handheld collapsible reflector has become a part of virtually every shooter’s toolkit. A translucent silk, white, silver, or gold reflector embodies the goal of most shooters to work simply and efficiently.

Since the dawn of photography a century and a half ago, however, the lowly reflector has not seen much in the way of innovation. The one major advance is the introduction of the modern-style collapsible reflector in the early 1980s. The versatility of the collapsible reflector evolved significantly when Westcott introduced a center-cut rectangular model in 2014, followed by a new circular version this year dubbed the Omega 360. Inspired by wedding still photographer Jerry Ghionis, the Omega 360 Reflector Kit is a simple, low-cost system that combines the functions of a traditional reflector/bounce and silk, with a ring-light effect for capturing compelling talking heads and portraits.

The collapsible reflector hasn’t changed much in the last 40 years – until now. The Westcott Omega 360 reflector kit features five fabrics that can be configured with or without the center cut out.

Unlike traditional single-surface reflectors, the Omega 360 features five removable center disks for different looks — black, white, diffusion, translucent, and a mini reflector. The Velcro-fitted 13-inch inserts detach quickly to create a shoot-through design that lends itself to a range of flattering effects. The center cut out, for example, can help mimic the look of a main light and backlight simultaneously from a single source (like the sun). Given the most common interview talking head applications, it will find ready use in corporate and nonfiction programming, including news magazine shows.

Fill Where You Want It, Negative Fill Where You Don’t

In my experience, the reflector’s black surface or negative fill adds drama and panache to otherwise flat or lackluster portraits. Working with sensitive digital cameras, we tend to spend more time excluding light from a subject than adding new light to it. The negative fill option in the Omega 360 can be useful for improving a subject’s three-dimensional look and feel.

Skinflints, in particular, might be inclined to simply remove the middle section from an existing reflector in order to achieve a comparable effect. Your jury-rigged reflector, however, isn’t likely to perform as elegantly or last as long as you would hope. Keep in mind the Omega 360 kit is hardly going to break your bank; at $129 it seems hardly worth resorting to such schemes.

Moreover, the Omega 360 reflector is very rugged — probably more than what you’re using now — with a lifetime warranty on its flexible steel frame. The double-riveted construction is a good thing, as the metal bands inside my old collapsible reflectors have long since fractured under the twisting stress of my gorilla Bart Simpson-like grips and overzealous production assistants who claim to know but never actually learned to properly collapse the reflector.

The five-in- one kit can mimic the functionality of a traditional ring light.

Photos by Jerry Ghionis

An actual ring light will produce a very flattering effect on subjects, especially aging celebrity types who benefit from the shadowless illumination. But a proper ring light can be expensive, and mounting a ring light on compact cameras that lack a proper rod system is an inconvenient hassle. All of this makes the Omega 360 valuable on any set, large or small.

Leave a Reply