Achieving Clarity and Portraiture — Without Sacrificing Depth of Field — Through Virtuosic Large-Format Filmmaking

Murder on the Orient Express, Agatha Christie’s iconic tale of mystery aboard the legendary train, is back on the big screen, courtesy of director Kenneth Branagh and 20th Century Fox. Branagh, who also plays famed detective Hercule Poirot, teamed with director of photography Haris Zambarloukos, BSC, GSC on a new retelling of the yarn with a cast including Daisy Ridley, Michelle Pfeiffer, Penelope Cruz, Willem Dafoe, Judi Dench and Johnny Depp in key roles.

Zambarloukos and Branagh have made a string of visually striking films with wide-ranging subject matter and style, including Sleuth, Thor, Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit and Cinderella. For Murder on the Orient Express, they made a bold decision to shoot on 65mm film — a format that Branagh and cinematographer Alex Thomson, BSC had employed to striking effect 20 years ago on Hamlet.

“The story led us to the 65mm format,” says Zambarloukos. “For me, the choice of format is less technical and more about the sensory experience and whether it’s right for the story. We wanted clarity and a kind of portraiture on the faces of these characters, while retaining an awareness of the luxurious train and the stunning scenery that surrounds them — without needing to cut to an exterior wide shot.”

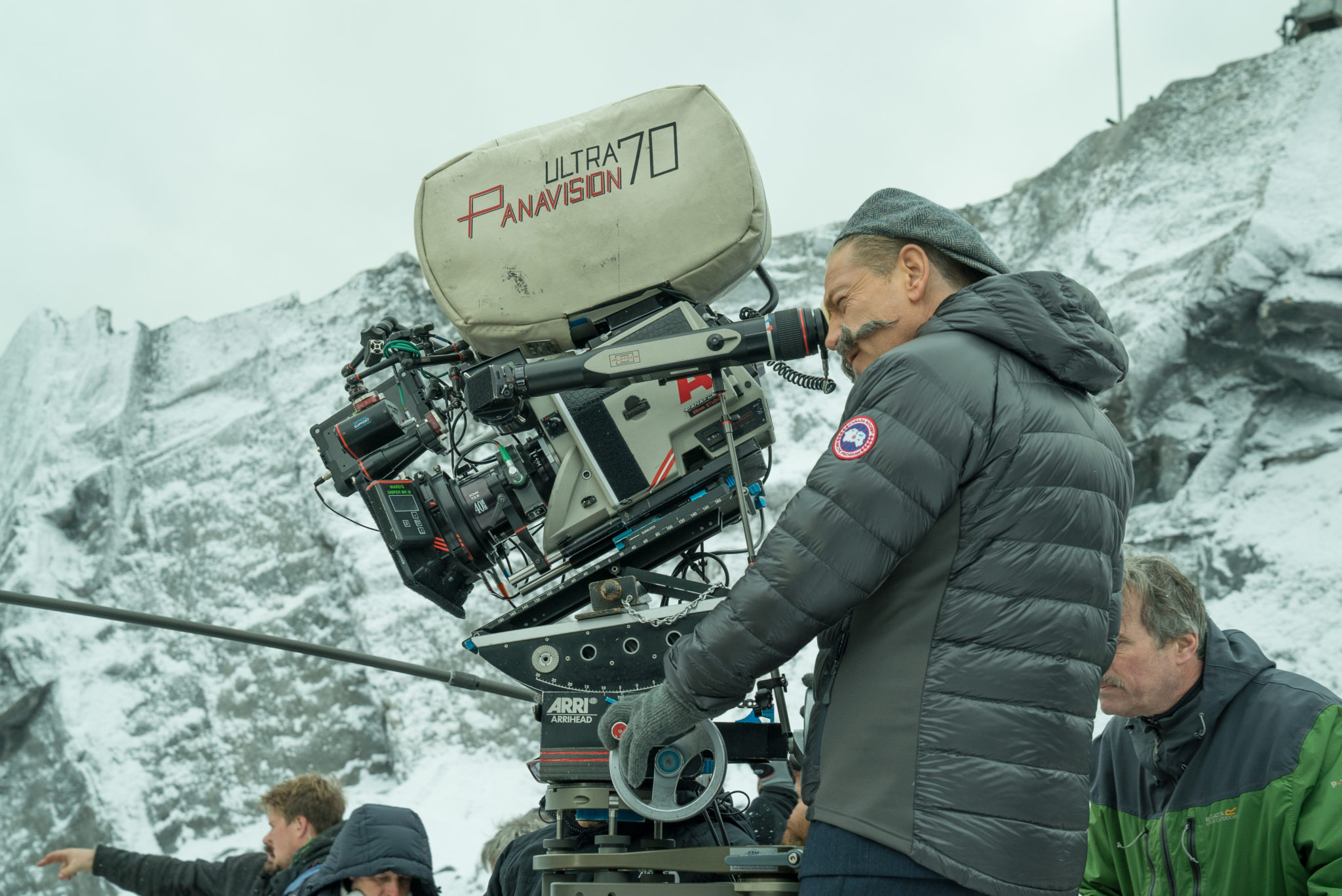

Haris Zambarloukos, BSC, GSC

All photos by Nicola Dove

The filmmakers enlisted Panavision to help achieve their vision. Every aspect of the company was involved — optics, engineering, cameras, and global services. Three high-speed and two studio-mode Panavision System 65 cameras, battle tested on Dunkirk and The Hateful Eight, were completely refurbished with finely tuned movements, new mirrors and motor drives, and were outfitted with improved viewing systems. Panavision Sphero and System 65mm lenses were adjusted by Dan Sasaki to Zambarloukos’ specifications. And special Sphero 65mm lenses constructed from scratch delivered T2.8 or faster speed as well as better edge field illumination, improved flare and glare control, and improved close focus capability, especially for wider focal lengths. By the end of the shoot, an improved HD video tap had been implemented on all the cameras.

All these tools were intended to serve the detailed vision that Zambarloukos and Branagh devised for the film. The 65mm format worked in concert with film grammar that featured fewer cuts. Zambarloukos estimates the film has an average of 150 edits per reel, a fraction of what’s considered normal in current cinema.

“When you shoot 65, you don’t want to suppress it,” he says. “The enhanced definition works so well when you’re committing it to film. In still photography, the most intimate portraits are the medium-format, Hasselblad type of images, where you simply observe someone’s face. You don’t force it. You let it speak for itself in a way. The richness of the image means that the static frame doesn’t become boring. This film is about a man interrogating 12 suspects, and the performances become a sensory observation. The large format seems to communicate the human condition. The slightest facial movement makes such a big difference. You really feel like you’re under the microscope, the same way Poirot puts these characters under a microscope.”

Haris Zambarloukos, BSC, GSC

All photos by Nicola Dove

The camera is often on the move. At various times, the crew used Steadicam, Technocrane and Libra heads. “We designed scenes that encompass all these great actors in one roaming shot,” says Zambarloukos. “You really take it all in, which is harder to do with a smaller gauge. When you get them all in one orchestrated shot, without cutting, in 65mm, you really feel their presence. In a way, because it’s such a different experience, the combination of the format, lenses and film emulsion bridges the worlds of cinema and live theater.”

The shoot was mounted at Longcross Studios, about 25 miles west of London, where train carriages were perched on a three-story viaduct for some scenes. Plate shots captured digitally in New Zealand were projected on LED screens to provide the requisite breathtaking scenery.

The improved close focus allowed for shots in the train cars that revealed the subtleties of the actors’ art, and the improved edge-to-edge illumination ensured that the characters were placed in the grand surroundings. But the choice of format and shooting style are interwoven even more intricately, according to Zambarloukos.

Johnny Depp in Murder on the Orient Express.

All photos by Nicola Dove

“Rather than leading the audience with shallow depth of field, our approach was more often to let the eye roam, and let the audience find where they want to go,” he says. “It’s a more direct method, just as Poirot is a very direct character. He looks straight into people, trying to determine morality and point out the consequences of vengeance.

“So, to me, it was never going to be a film where you’re searching for things,” he says. “You make bold decisions and you stick to them. That’s how this film was made. It could only be cut a certain way as well. Of course, we chose our moments for isolating a character, but shallow depth of field can be distracting. It didn’t feel right. There’s a certain confidence in an image with reasonable depth of field, and that relates to confidence in the character.”

The 29mm Sphero was on quite often, as well as the 40mm. Longer focal lengths were used in specific situations, but Zambarloukos says the wider lenses had more 65mm flavor. “A mid-shot on a 40 or a 50 in 65 [mm format] is something exceptional,” he says. “The amount of detail in the face is as if you were doing a head-and-shoulder shot. You are completely aware of the costume, the body language, the eyes and emotions, and yet you are completely aware of the space. You begin to see how the classic films were made, and why they were made that way.”

Although Murder on the Orient Express is considered the prototypical whodunit, the filmmakers were more focused on the mystery of the characters.

“We were much more interested in creating a film about why they did it, and asking whether it was worth it,” says Zambarloukos. “Although this film was definitely made as entertainment, we want the audience to undergo a cathartic process, as you would with a Greek tragedy. Our various filming techniques were designed with that ultimate aim in mind — to explore the human condition.”

Penélope Cruz in Murder on the Orient Express.

All photos by Nicola Dove

Color in the film is generally lush and vivid to communicate the rarified world these characters travel. As melancholy seeps into the story, darkness becomes more prevalent. But for some scenes, black-and-white imagery helps communicate the directness and moral clarity in Poirot’s worldview. Kodak doesn’t currently make black-and-white emulsion in the 65mm format, so Zambarloukos shot color and drained the images to black and white in the DI.

“That was a lovely thing to do,” says the cinematographer. “The results are still incredible. And it’s interesting — it’s a very different way to create black and white, because you can assign a contrast level to a specific color. It’s a very detailed, precise way of creating your final black-and-white look, and we’re taking full advantage of that in our DI.”

Zambarloukos points out that the format requires top-notch crew in every department. He credits focus pullers Dean Thompson and Peter Byrne, camera operators Roger Pearce and Luke Redgrave, and the rest of the camera and grip crews. Panavision’s Robert Aguirre was on set from start to finish to ensure a smooth shoot.

Director Kenneth Branagh

All photos by Nicola Dove

“The virtuosity required to make it work and seem effortless is hard to explain,” says Zambarloukos. “And it wouldn’t have been possible without the massive support of Panavision, Kodak and FotoKem. That support made it easier for Fox to agree to the format. They knew we were being looked after. And it’s important to give credit where it’s due — the people at 20th Century Fox have been terrific every step of the way, including the 70mm prints. There are some great people there who enjoy making films and doing it right.”

Working with 65mm film requires intent in every aspect, from every department. “As a crew, we’ve really had to reach another level of our performance doing this film,” says Zambarloukos. “We’ve been changed by the experience. Shooting film, and shooting 65mm, requires you to imagine and think carefully before you place your camera. A centimeter left or right, a 40 versus a 50mm lens, makes a big difference. We were careful and measured about everything. We tried to think about what we wanted to achieve with every shot. And I think we’ve really achieved something special.”

Murder on the Orient Express opens today in North American theaters.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.