Holly Olshefski

Jonathan Olshefski’s Quest follows the Rainey family over the course of 10 years, although the central portion of the film takes place in the run-up to Obama’s election, his subsequent years in office and Trump’s campaign. Christopher “Quest” Rainey owns a recording studio and works as a music producer, and his wife Christine’a, nicknamed “Ma Quest,” who works at a women’s shelter. Their son William becomes ill with cancer, and their daughter loses an eye to a random gunshot outside their house.

It would be easy for a much more sensationalistic filmmaker to create a stereotypical portrait of working-class African-American life and the North Philadelphia neighborhood where the Raineys live from this material, and Quest acknowledges that their problems are very real. But it gives the Raineys enough time to show their life in a three-dimensional manner; although the film is well under two hours, it feels like the first epic about American life under Obama. Olshefski, who is white and acutely aware of his status as an outsider and the need for him to collaborate with the Raineys in order to create a respectful documentary, served as his own cinematographer and sound man.

StudioDaily: You did your own sound. The sound design is quite creative, with sound from one scene layered over another one. Was that all your own work?

Jonathan Olshefski: In terms of the sound recording, I was my own sound person for the whole time. Late in the game, there’s some sweetening and some different interesting things in the sound mix, but for the most part it’s just me and what I recorded. It’s important to use sound in a subtle way to amplify these moments and not overwhelm the emotions. That’s the direction I was going for.

Since the shoot took years, did you edit as you went along?

Yeah. There’s an early version of the film in September 2007. But there were other layers to the film that I experienced in a year and a half when I was doing a photo project. Then the 2008 election came along. I just kept feeling like editing the material wasn’t always reflecting what I experienced. There was still more. The social aspect of tagging along with the family with a camera was more telling to me than sitting behind a computer trying to figure out this puzzle of a structure. When I got overwhelmed with the edit, I spent more time with the family and shot more stuff that I would try and figure out later. I kept pushing ahead with that. I kept pushing things back. I finally wrapped up in January.

Patricia “PJ” Rainey, Christopher “Quest” Rainey

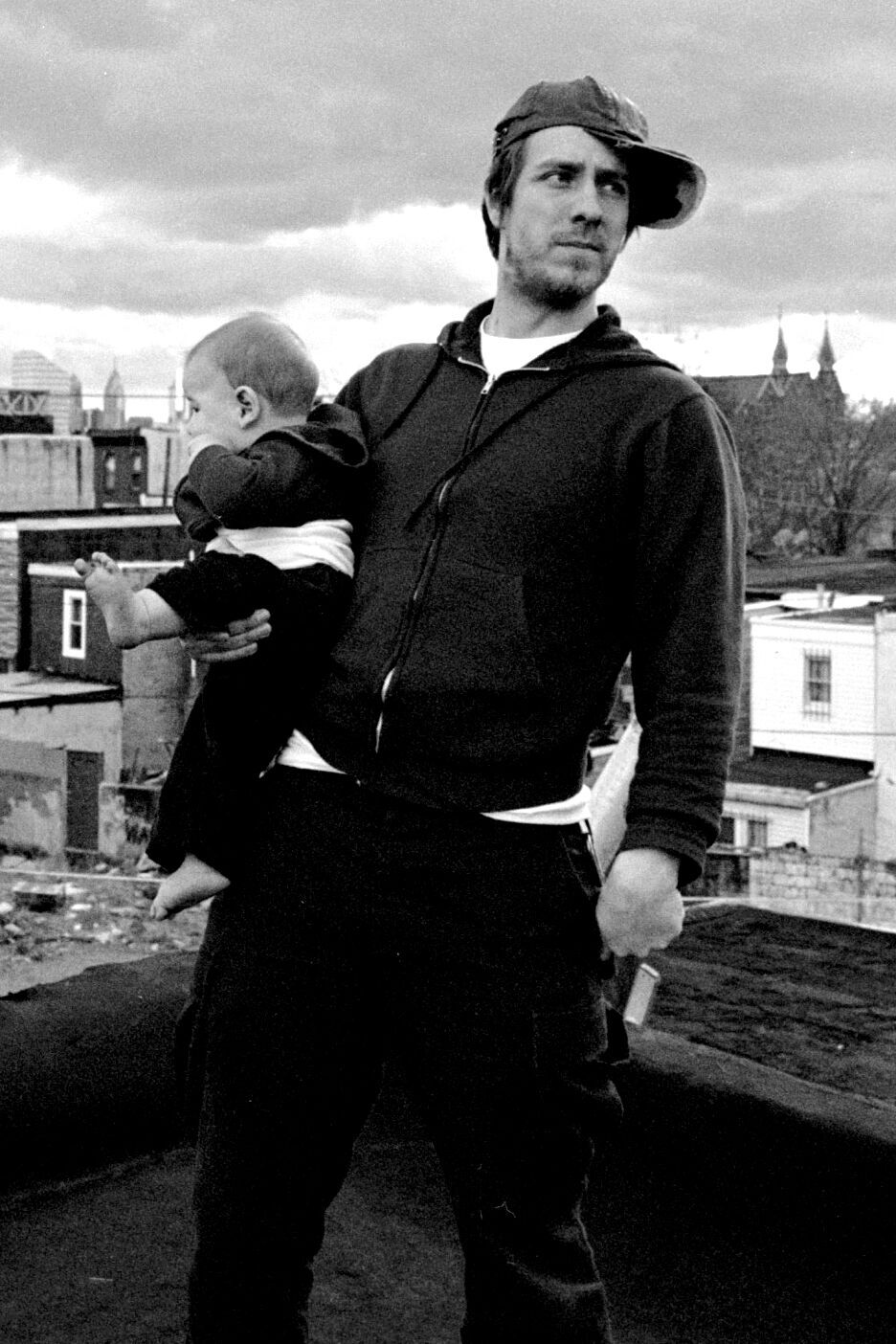

Jonathan Olshefski

You depict hip-hop in a fairly unusual way, as an organic part of a community. Films about it tend to center on rappers shooting for stardom. You show people making $30,000–40,000 a year as producers and rappers continuing to do it for years.

I really wanted to show the people behind the personas. I wanted to get to the layers of vulnerability behind these artists. They’ve experienced a lot of hard things in life, and hip-hop is a way for them to express that. That’s what I wanted to focus on: hip-hop as a way to lead in to the nuanced lives they live. The studio is something that’s happening now in real time that’s really special and beautiful. It gets into how you define success. Are you successful when you get signed by this big label and make all this money? I think there’s something successful about meeting people, bridging gaps and making recordings. That’s the essence of Christopher’s studio. People do sometimes wind up getting signed. That narrative is there. But they’ve already achieved something. I wanted to highlight that. There’s dreams of moving forward, but what they’ve already done is extraordinary and beautiful.

After a year of Trump in office, Quest now seems like a film that looks at the Obama administration from a historical period. Were you self-conscious about that as you were shooting it?

I felt like 2008 was a historical moment, and it was interesting to see it from the perspective of this family, not even knowing if he was going to get elected or not. There are some resonances. What was going on in the political scene and American culture affected the neighborhood. There’s a barbershop scene with all kinds of Obama paraphernalia. The barber is even wearing an Obama/Biden shirt. The big political things make their way into a community and how it understands itself. They felt they might be listened to in a way they weren’t before. Then we ended up with Donald Trump. All of a sudden, this other narrative has been validated by voters, despite the community not wanting to be seen this way. There are these little moments that work their way in. They provide a chronology. We’re in a country that wonders if we’re going to have a narrative of hope and connection or fear and alienation. Those narratives are smashing against each other right now, and we have to decide which one we’re going to go with. Do we go with the Obama narrative or the Trump narrative?

Patricia “PJ” Rainey, Christine’a “Ma Quest” Rainey, Christopher “Quest” Rainey

Jonathan Olshefski

You shoot some pretty intimate moments between Christopher and Christine’a Rainey, especially discussing their daughter’s sexuality. Were there things you left on the cutting room floor because they were too emotional or private?

I think we cut things out because they shared personal information. Our goal was to accurately depict this family in all their complexity. There’s something raw, real and authentic about them talking about their daughter’s sexuality. Viewers may disagree with them in terms of their approach and attitude, but it reflects where they were at the time. And they’ve grown and changed. But the purpose of the film is to make connections and spark dialogue. It can be a catalyst for that. To get to your question about cutting things out because they were too personal, we looked more about how to bring certain things out and make this family and community to viewers in a complex and layered way. There’s personal stuff that made sense. There’s personal stuff that didn’t make sense to help tell a love story between a husband and a wife and a family and a community.

There’s been a lot of talk in the past year about what kinds of stories white filmmakers should be telling. You recognize the danger in the neighborhood the Raineys live in and devote a lot of time to their daughter getting her eye shot out while sitting on the street, but you show Donald Trump speaking about what a hellhole African-American neighborhoods are and Christine’a saying he doesn’t know what the hell he’s talking about.

Again, that’s a narrative imposed on the community even by the local press. They cover tragedy, but they miss out on the love and complexity. There are families trying to love each other and raise their kids when the system fails. To me as a white filmmaker, I was already familiar with the neighborhood before I met the Raineys. I don’t think the neighborhood should be defined by its obstacles but by the people who are there. It should be defined on their terms. As a filmmaker, I wanted to reflect the perceptions of my subjects. There are hard times, but there’s a lot of love, beauty and laughter. I wanted to represent its complexity, as opposed to the one-note, sensationalized depictions you usually get. You do have white, privileged filmmakers swooping into marginalized communities and reinforcing stereotypes. I wanted to reflect the way the community sees itself.

Jonathan Olshefski

Carina Romano

There’s a somewhat free-floating quality to the camerawork. Did you ever use Steadicam?

I never used a Steadicam or anything like that. Everything’s hand-held. When I moved, I tried to do it in such a way that things were not unbearable to watch. As a one-man-band filmmaking process, I didn’t want a lot of apparatus between me and my subjects. I had a small camera with a monopod. I felt that with me being just one person, I could tag along and the moments would just be what they were there. I was just along for the ride.

How did the support of PBS come about? Did they place any strings on you in terms of content or length?

In terms of the theatrical version of the film, me and my producer felt that was the right length for it. For PBS, we do have to cut the film down to 82 minutes. So we have to cut 20 minutes out for broadcast. That’s just something we have to do for our biggest funder and co-producer. In terms of content, we’ve shown them cuts along the way and they’ve respected our editorial vision. They’ve given us notes along the way and raised questions and shared their perspective, but they’ve respected our direction. The film was a no-budget one-man-band production for about 8 years, and then I was starting to finish it at a high level. I was trying to write some grants. I was accepted into the IFP Documentary Lab in 2014, and they said “There’s something special here, there’s something beautiful here, but it’s not going to reach its full potential if you are just doing it on your own with no budget. You need to raise some money and build a team around it for it to be as beautiful as it could be.” They encouraged me to write some grants and build a budget. I got accepted by ITVS, which is a division of PBS. Then I was rejected twice. I applied three times. On the third time, I got accepted. It’s amazing to work with public television, which has a mission to share stories that aren’t being told. I feel like Quest is a film that fits in with that.

Your film has been compared to Hoop Dreams and Boyhood. What films were models or influences for you?

Well, the Steve James approach to filmmaking with Hoop Dreams: spending time with people, showing people grow and change. He takes a relation-oriented approach to filmmaking. It’s about relationships with people first, filmmaking second. There’s another film called Dark Days, which gets a really deep relation between the filmmaker and community. You can tell when directors are voyeuristic or sensationalistic gawkers. These are folks living in New York subway tunnels, but it shows a spectrum of human emotions. You see some pretty harsh moments, but also people laughing and joking. Wherever you are, there are happy moments and there are hard moments. Films that are layered and honor their subjects are ones I wanted to emulate. I want to avoid films where I walk out of them feeling uncomfortable and awkward. Why am I here? Why am I watching people? I feel uncomfortable about the relationship between the filmmaker and the subject. I didn’t want to use the family to flex my own creativity and message. I wanted to let them say their message and have us say it together.

Christopher “Quest” Rainey, Isaiah Byrd, Christine’a “Ma Quest” Rainey, Patricia “PJ” Rainey

Carina Romano

How much has the film been shown in Philadelphia, and how have local audiences reacted?

We’ve screened it in Philadephia in August, in the neighborhood where the film takes place. The filming has been a process for 10 years. So people who’ve seen it being shot for that time could finally see the results. Residents of North Philly could see themselves and their neighborhood depicted in a way that shows their facets. They felt seen and heard. We were able to have a great dialogue after the screening. Then we’re opening in the entire city. Our Philadelphia premiere is happening downtown. I hope the larger city responds well. It’s truly a Philadelphia film. I hope people fall in love with the Rainey family, in all their complexity. I also hope they’re inspired to do some work to bridge some of the gaps, to work hard to bring some of the healing that’s needed. Philadelphia is a beautiful city, but it has some significant issues.

How is the rapper Price, whom Quest tries to mentor through his problems with alcoholism, doing now?

The ups and downs continue. He was a part of the North Philly screening, and he got to share and talk. He’s working. He continues to make music. But he struggles with addiction still. It’s a long-term illness that you have to deal with. He’s still trying to stay sober.

Quest is playing at the Ritz at the Bourse in Philadelphia. It opens today at the Quad Cinema in New York City and on December 15 at the Laemmle Monica in Los Angeles. More playdates in different cities are listed at the First Run Features website. Photo at top of page: Colleen Stepanaian

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.