Where Analog Meets the Digital Canvas

It goes without saying: Fewer shooters these days have any experience with film. Many ‘film’ schools have long since given up the filmic ghost. Indeed, throughout the industry, from commercials to entertainment, the digital world has completely taken over, which leads one to wonder if film references and ‘looks’ are still relevant at all.

I recall years ago working in the camera department on The Glass Menagerie, a feature film directed by Paul Newman, and shot exquisitely by the late Michael Bauhaus ASC. Michael chose to shoot the 1930s scenes on Agfa XT320 stock, which he felt best conveyed the warmth and mood of the Depression era story. In contrast, for the few contemporary scenes, he opted for the cool, less dreamy look of Kodak stock 5297. Film shooters have long understood the nuances of various emulsions, and how film type and filters can impact the visual story.

Since the dawn of cinema, shooters have exploited the unique character of film to further their visual storytelling goals. DFT’s Film Stocks 3 enables today’s all-digital shooters to re-create a compelling high-end film look like this one from James Cameron’s Titanic.

Paramount Pictures

Today, of course, we have many powerful digital tools at our disposal, and we are no longer constrained by the handful of film types or smattering of glass filters we happen to have in our kits. We have a nearly infinite range of options to affect a project’s look, including a bevy of film emulation plug-in filters from a variety of developers.

So how is Digital Film Tools Film Stocks 3 relevant to current generation shooters who don’t know the difference between Kodak 5219 and Fuji 8514?

There are basically two types of potential users of Film Stocks 3: Folks who seek to match a particular look in a production, say, for combining new and old footage, and those who wish to use the tool stylistically to craft a custom overall look consistent with the storytelling.

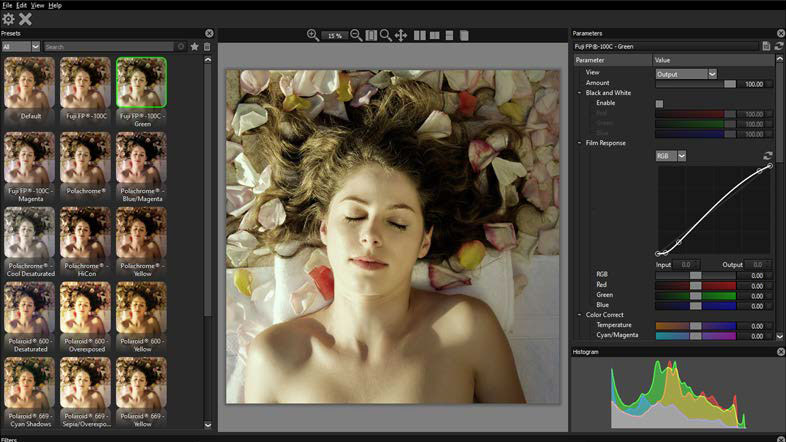

Other film emulation software employs 2D and 3D LUTs alone to achieve a desired look. Film Stocks 3, improving on Tiffen’s former DFX software, utilizes both color correction (top) and film response (above), incorporating controls for nine discreet functions, including sharpness, grain, and diffusion level.

At its core, Film Stocks 3 emulates over 300 different color and black and white film processes and emulsions from Kodak, Agfa, Ilford, Rollei, and Polaroid. Improving quite dramatically upon Tiffen’s former DFX software (which Digital Film Tools created), FS3 features a notable, easy to access library of 89 color grading presets from celebrated movies like 2001 A Space Odyssey, Apocalypse Now, Saving Private Ryan, and Titanic. The once-faddish lab processes, like bleach bypass and cross processing, that produce distorted, exaggerated colors, are also included, as is a trendy grunge filter to add hair, dirt, scratches, and other defects, like gate weave and flicker.

Perhaps on a more useful note, Film Stocks 3 features a pair of nifty Technicolor Three-Strip and Two-Strip filters. Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator, photographed by Robert Richardson, ASC, is one of the seminal preset looks offered in the Film Stocks 3 library. Robert Legato, The Aviator’s VFX supervisor, wanted to simulate the 2–strip muted, slightly desaturated, look in the 1920s-40s era movie, and ran the original film footage through a custom two-strip filter, which he created. Later, Robert worked with Digital Film Tools to replicate The Aviator‘s Two-Strip Technicolor filter, which is included in FS3, as well as the company’s DFT v1 set of filters.

Referencing film emulsions from A Ilford and Kodak, Film Stocks 3 features 300+ analog film presets and 89 color grading presets for iconic feature films like 2001 A Space Odyssey, Apocalypse Now, Blade Runner, and War of the Worlds (above).

In this way, Digital Film Tools’ software is different than other film emulation plug-ins. Drawing on its long history of creating special FX for feature films, the company employs a proprietary analyzer that looks at not only brightness, color, and texture, but also the sharpness, grain, and detail layers, in the film image. Separating out the components, DFT can determine in far greater detail how an original film image is constructed.

This approach, designed to withstand scrutiny at high magnification on a cinema screen, is therefore extremely accurate. While other makers’ plug-ins rely on color correction alone, the majority of the look presets in FS3 allow full user manipulation of an image’s structural components as well.

In the digital intermediate suite, savvy operators would often specify the manufacturer and type of print stock to ensure proper color output and density when recording back to film. With the advent of digital cinema and DCPs, the demand for film output has for the most part disappeared, but the lessons learned with respect to building a desired look remain as relevant as ever.

For shooters, this points to the larger discussion, namely, how much of the look and control of the image should be done in-camera, and how much should best be left for post-production using software like Film Stocks 3?

Given the power of today’s color correctors, especially the new four-way corrector in Film Stocks 3, most imaging functions lean towards applying the desired control in post. Clearly, in most cases, a post-camera solution offers many advantages, but there are times when post manipulation of the image is either not yet practical or ill advised.

Underlying the tool’s power and high-end Hollywood pedigree, Film Stocks 3 features 32-bit float processing to ensure a non-destructive environment for manipulating film images. The polarizer with its many options is displayed here.

A polarizing filter is one such case as it can only be applied effectively at the time of image capture. For example, consider the polarizing filter included with Digital Film Tools’ DFT v1 software (unfortunately, it’s not a part of Film Stocks 3). It can simulate the polarizer’s effect to some degree, by darkening and/or increasing the saturation in a blue sky, for instance. It does not add back, however, the detail lost, say, in a blown out sky, nor does the plug-in suppress the highlight reflections from glass surfaces that would have been attenuated, or eliminated completely, with an optical on-camera polarizing filter.

That’s not to say Digital Film Tools hasn’t tried to produce a more effective polarizer. The problem is, given the current technology, software-based polarizers produce a lot of artifacts, and the present strategy of combining multiple layers and data sets works poorly for moving video with constantly shifting planes, sun angles, and noise patterns. A comparable state of affairs applies to some new camcorders like the Sony FS7 II fitted with an electronic variable neutral density filter (VND); the camera sensor can mimic to some degree the attenuation of a physical glass ND but not completely.

A diffusion filter is tough to mimic in software because most scenes require color-correction in addition to the smart application of halation. The effectiveness of any film emulation software is not 100%. Notwithstanding the technical prowess of Digital Film Tools, the emotional component of motion picture film is hard to quantify.

Software-based diffusion also presents a daunting range of challenges, but in this area DFT has had much greater success. As shooters, we understand that the halation from a diffusion filter increases with the amount of backlight and the lens’ focal length. The Mist filter in DFT v1 (also not included with Film Stocks 3) offers shooters a key advantage: the ability to maintain a constant level of diffusion when moving between various focal length lenses.

Moreover, the Mist filter applies halation based on the highlight values in a scene. A slider adjustment generates a matte internally that suppresses the halation in the darker areas of the frame while the brighter highlights logically display increased halation. In this way, the software accounts for a strong backlight, varying the effect just as in real life.

When shooting with a tinted filter like a coral, experienced shooters have long understood that the image’s highlights reflect the tint to a less degree than the midtones or shadows. The FS3 software adds a setting to control the highlight application of the tint, a detail reflecting the care and insights that have gone into the tool.

For shooters with little familiarity with film emulsions, DFT’s Film Stocks 3 can be a potent tool nevertheless for matching a specific look, or creating a new custom look using the built-in library as a starting point. The library, referencing some of the greatest movie looks of all time, offers broad capabilities and controls, not to mention valuable lessons to the latest generation digital shooters. Tintype? Daguerreotype anyone? It’s all in there.