Scaling Kong Up, Working in Natural Environments and Paying Homage to Willis O'Brien's Original

The Visual Effects Oscar nomination for Kong: Skull Island is senior visual effects supervisor and second unit director Stephen Rosenbaum’s third. He has received two Oscars and two BAFTAs for Avatar and Forrest Gump.

The first film Rosenbaum worked on was The Abyss at Industrial Light & Magic. He was a CG artist there for Back to the Future Part II, Terminator 2, Death Becomes Her, and Jurassic Park before becoming a CG supervisor with Forrest Gump. From ILM he moved to Sony Pictures Imageworks for Contact and other films, back to ILM to help supervise The Perfect Storm, and on to Weta Digital where he supervised I, Robot, The Water Horse, and Avatar.

Jordan Vogt-Roberts directed Warner Bros’ Kong: Skull Island, which puts a monstrous Kong so big that only body parts can fit in some frames on a primordial island filled with unique and equally enormous creatures. It was filmed largely in Vietnam. In addition to the Oscar nomination, Skull Island received four VES nominations — for outstanding visual effects, simulations, animated character, and compositing — and an Annie award nomination for character animation. Released last May, the film earned $566 million at the box office.

Also nominated for a Visual Effects Oscar are Scott Benza and Jeff White from ILM and special effects supervisor Michael Meinardus.

ILM says this Kong: Skull Island VFX reel includes the most complex hair simulation it has ever created.

Youtube/ILM

Studio Daily: Why do you think your colleagues voted for Kong: Skull Island to receive an Oscar nomination for Best Visual Effects?

Stephen Rosenbaum: The competition is so good I was surprised we were nominated. But Kong is a lifelong iconic character for visual effects artists, one of the great creatures we could work with. There can never be enough movies about King Kong. I think people are partial to large creature movies. They’re fun if done well. The action is there.

And to be honest, ILM’s work was fantastic. They pulled out all the stops. We had a huge challenge in that we made a conscious effort to design Kong as an homage to the Willis O’Brien character, and I think that resonated with our community. I think they also respected and appreciated that we had a healthy smattering of other creatures that had a purpose, that weren’t just visual eye candy. [Director] Jordan [Vogt-Roberts] didn’t want the movie to be just about King Kong. He wanted the island to be a character with Kong as its god. He wanted to make sure we enjoyed the beasts on the island and I hope that also contributed.

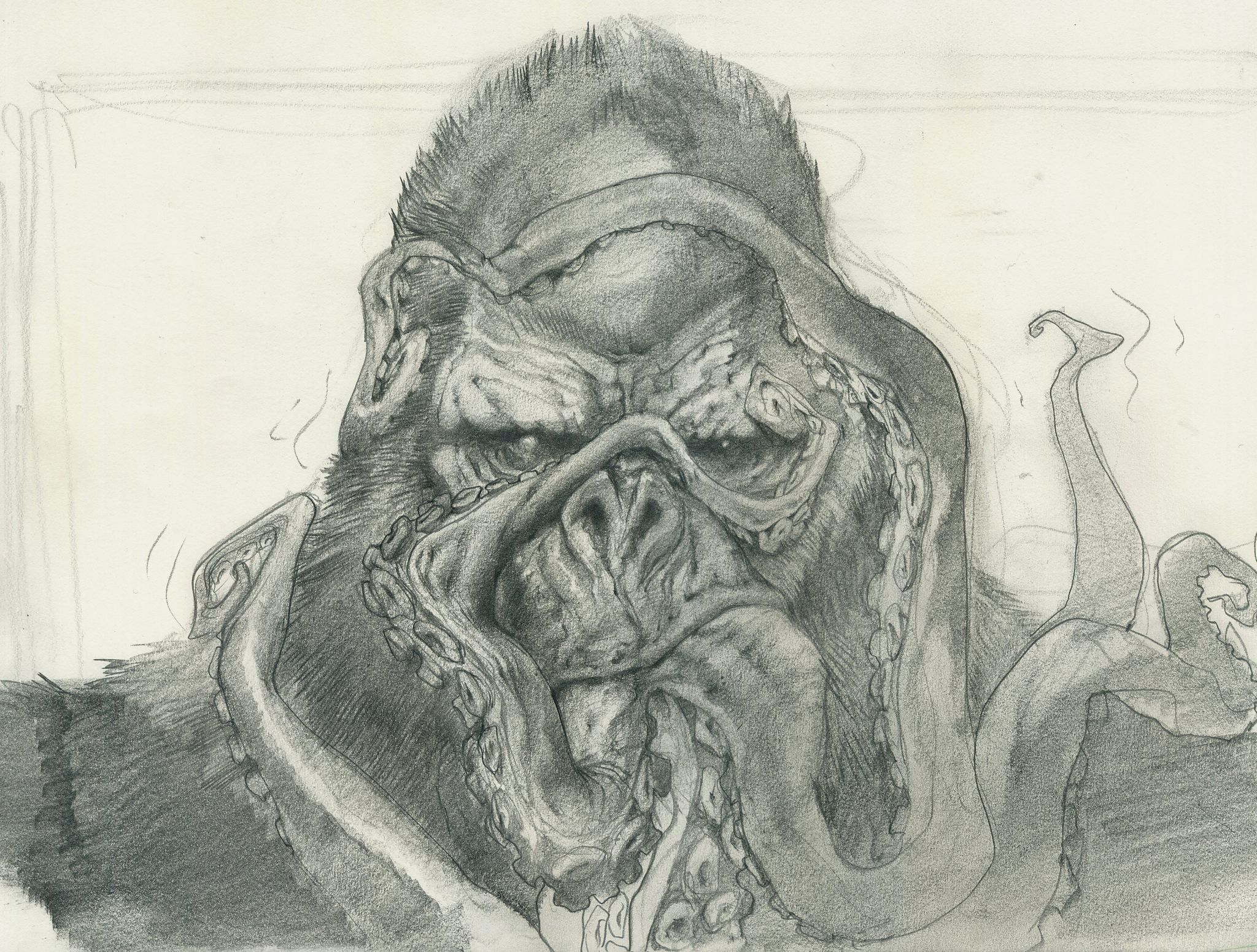

The King Kong of Kong: Skull Island was meant in part as homage to Willis O’Brien’s original (inset).

Courtesy of Legendary Pictures/Warner Home Video

Tell us more about Kong.

I think most people go back to the original when they think of King Kong. That original character was more a monster than a gorilla. We wanted to preserve that original Willis O’Brien silhouette. We made our Kong bipedal. He has a huge head, big teeth and eyes. His design reminds us that he was some form of primate, but more importantly is a monster. One, in our case, we can evoke some sympathy for. We tried to build character into the creature, to bring some type of sentient qualities to his performance.

What was your schedule?

When I joined the crew in October 2013, they had two movies’ worth of concept illustration and creature designs, so that was fun. Stefan Dechant was the production designer, someone I’d worked with on Avatar when he was an art director. He was also at ILM in the early days.

This was Jordan’s first big-scale effects movie, so to get him acclimated to that process we brought in Halon to do previs and let Jordan play. He designed the “flight of the Valkyries” sequence, where Kong attacks a fleet of helicopters. Those early days lasted until May/June 2014 when we got our first solid script. Jordan’s style was very much about the visual narrative, about establishing a visual narrative around the creatures of the island before scripting out the story.

Establishing a visual narrative before scripting the story?

We didn’t start with a script and build visuals. This was the other way around from the way things are usually done. We wanted to leverage the locations and use the environments to inspire the story. We did a lot of scouting from late 2013 through spring 2014 — Iceland, Cambodia, Thailand, Hawaii, Vietnam — searching for inspiration. We talked about which creatures could work in what environment to inform the story and process. It was very much that frame of mind, which was a welcome experience. By spring 2014, we had three or four movies’ worth of narrative imagery: concept art, storyboards, previs, location scout photos. We would lay them out across the walls and think about what creatures could work in these environments. Then, for a lot of the scenes, the script was leveraged from the storyboards, concept art, and previs. It was largely developed with discrete components that writers would string together into a contiguous storyline.

Give me an example of a scene derived from the environment.

We went to Vietnam maybe four times before we shot there. One time, we were in the area of Ha Long Bay and stumbled across a lady who managed a stunningly scenic fish lagoon. The scene of Kong eating the squid/octopus creature was inspired by what we saw in that location. We took lots of photos and then went back to the office and pulled a couple of orphaned but beloved pieces of artwork that had Kong wrestling with a Kraken-sized cephalopod. We then figured out that this would be a great place for the audience to witness a couple of character moments for Kong. The story points were based on just the artwork and that amazing location.

Concept art showed Kong eating an octopus.

Courtesy Legendary Pictures

An example of how the locations inspired creature design?

We were scouting in some bamboo groves. As we were standing in the middle of these dense groves, we wondered, what could we shoot there? We looked around and thought, what kind of creature would camouflage itself in this environment? What if the stalks were legs? What would we do with the bodies? The bodies could be just above the leaf canopy, so we wouldn’t see them. We’d only see the movement of a leg if they took a step. They’d wait for prey. That was literally how the design of the bamboo spider came about. A lot of our creatures were location-inspired. Of course, we had to think about how to move the story forward in the process.

How many creatures are on Skull Island?

We had originally designed a good three dozen creatures, but the day came when we realized we couldn’t fit all of them into one movie. We ended up with about nine creatures and variations. Kong, the water buffalo, the skull crawlers, the bamboo-legged spider, flying creatures, a stick creature, a few other quadrupeds, and of course, the octopus/squid creature.

Was the film shot entirely on location?

We wanted to do as much as we could on location. All told, we had maybe a week’s worth of green-screen work. The rest of the time we were in the wilds of the jungle.

Kong on Skull Island

Courtesy of Legendary Pictures

What did you use to represent Kong and the other huge creatures on location?

ILM had created an augmented reality app that ran on an iPhone or iPad. It functioned as a director’s virtual viewfinder to help visualize how our oversized creatures could perform in a live-action environment. When we were scouting, we could look through a camera lens and overlay Kong or other creatures we had mocked up and talk about how we would compose them in an environment. We’d overlay the CG characters in the environment and could get a good sense of how we could stage a scene. OK, Kong comes out from behind that mountain and squats in the water over there. It was awesome and extremely helpful. Even on the day of shooting, the actors, Sam Jackson, Brie Larson, Tom Hiddleston, could see in the iPad where Kong goes, and could see their eyeline.

That app was the saving grace for us. It was spatially accurate. I could measure out 300 feet with my Disto laser measurer and position Kong in the app 300 feet away. Larry Fong [DP] could ask, “OK, what does that look like on a 35?” I could pop in the correct lens and check it out.

Did you augment the locations with CG?

I brought out a couple guys from ILM who used a variant of a Lidar scanner to scan terrain, bodies of water, aircraft, and even entire mountains — not just the jungle. We wanted to ensure that Kong’s scale was upheld by allowing him to move freely across all the natural features of the island. So, we effectively scanned large parts of what became Skull Island. The final battle was shot in a marsh in central Vietnam, so the ILM guys floated around on pontoons and laser scanned large swaths of mountainous rock walls. When skull crawler or Kong slammed into a mountain, we knew where they were. And we photographed the heck out of the locations. We used that material to extend or augment the environments.

This video offers more detail on the creation of Kong as a character from ILM.

Youtube/ILM

Kong is a furry beast splashing in water. Was that technically difficult?

It was incredibly complicated. ILM ended up expanding their existing hair simulation system to give them more control over localized regions of his body. A hairy leg in the water reacted differently than when it was above the water surface. Outside the water we’d see the fur collide against itself with relatively straightforward physically simulated properties. In the water, however, ILM could control just that submerged region to account for hair becoming more buoyant and flowing with a completely different isolated physical movement. The water dripping off the fur and darkening parts of it and off the octopus surfaces was also tricky to do. The design control the artists had over choreographing local regions of overlapping simulations was something I had never experienced before.

You mentioned that the director was new to visual effects. Did he appreciate all this new technology?

He’s a smart guy. He picked it up quickly. He had a good visual sense of how Kong would work in the environments and having ILM’s augmented reality app on location helped him better understand how to physically shoot creatures of such massive scale. He immersed himself in the previs world and could understand compositionally how the action would work.

There’s a reason why we call this part of the filmmaking process the bleeding edge. It can be long and drawn-out, with scientific brainpower and artistic skills often colliding. It takes patience. I don’t think he was expecting how much the two sides of the brain compete against each other every day. But he did well. We didn’t totally expose him to the granular levels we get to. If we were talking about fur sims, his eyes would glaze over. We couldn’t expect him to know how complex the process is — many levels of technology go into making it look real. But he had a good understanding that it’s a lot more complicated than modeling a furry primate creature and animating it through jungle terrain. He understood on a high level and was by no means afraid or put off by the underlying complexities of our work.

What did you learn from making this film?

Two things. What we talked about earlier — that you can get a good movie from an inspired visual narrative. We designed a lot of the creatures based on environments we visited and figured out smart ways to introduce them into the island narrative that would also move the story forward.

The other thing — for the past few years, I’ve done a lot of movies with motion-capture playing a dominant role in CG character performances. We made a conscious decision that this needed to be a keyframed movie. There were technical reasons, but it was principally a creative decision. We felt like this is a movie with brawling titans that has to be fun to watch. In order to do that, we needed to recognize that animators should have a big role in creature performance and the story-making process, and that this was well suited for keyframe animation, not stunt men in mocap suits. Nothing against stunt men or actors in mocap suits. But these are beasts, large creatures that should not have anthropomorphic motion. We had an opportunity to be stylistic, to make them more dynamic and fantastical. I’m glad we made that choice.

I have to mention Scott Benza [animation supervisor at ILM]. He was totally all over breaking down creature anatomies and figuring out each unique style of locomotion. The creatures are fun to watch, number one, and, number two, they all have physically realistic mass and movement. The believability of the creatures in this film is a tribute to his skills.

Tom Hiddleston and Brie Larson take cover.

Courtesy of Legendary Pictures

The best thing about working on the film?

Doing a King Kong movie was on my bucket list of movies I hoped to work on. I didn’t care what the movie was about. I wanted to do a King Kong movie. We went to beautiful locations. There was always a concern that the creatures would overpower the frame and become the dominant visual, but we were able to successfully intermingle our creature work into those beautiful environments so they became part of the island lore that featured the scenery.

The hardest thing?

I was worried about delivering a Kong that people would like to see. We went in with the idea of doing an homage and modernizing that familiar silhouette of the original King Kong, but I was worried. I wanted the design to be accepted as an homage and not a rip off. I think we came through with that.

Other than that … it was the very large leeches and extremely relentless mosquitoes and the overwhelming and overbearing heat we had to endure. Big snakes. Lots of spiders. Is that spider crawling up my leg poisonous? We definitely had those moments. They weren’t pleasant.

Those beautiful locations were unpleasant?

The joy of location work. There was this one moment in a marsh. We’re all in waders that go up to our chests. Thigh-deep water. I look down and see this thing that looks like a snake swimming toward me. I realize it’s a foot long leech. It bumps against my wader and keeps bumping into it. And then, of course, it’s inevitable that someone falls in and their waders fill up with water and who knows how many leeches now happily trapped against their new friend. The glamour of movies.

What are you working on now?

I’ve partnered with Simon Fuller who created American Idol. We formed a company called Vesalius Creations. We’re doing digital humans — virtual musicians — for augmented reality, virtual reality, and live events.

Crafts: VFX/Animation

Sections: Creativity

Topics: awards 2018 oscars 2018 oscars 2018 vfx supervisors VFX

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.