NAB Show New York reported “total registered attendance” of 15,097 industry professionals for the two-day conference and expo that took place at Jacob Javits Center in New York City last week. Show organizers didn’t report figures for last year’s show, but the 2018 number represents a slight dip of about 2% compared to 2016, when 15,404 were said to have registered to attend the event.

The relatively flat trend is appropriate for a broadcast industry that seems to be in a holding pattern at the moment. Yes, investment continues to take place in hardware that supports the next-generation broadcast standards defined in ATSC 3.0, but the transition is likely to take place incrementally over an extended period of time.

Why is that? Remember that the move to HD broadcasting was accelerated by a government mandate that broadcasters adopt the ATSC 2.0 standard. Some broadcasters flipped the switch sooner than they would have liked, and have been working to recoup their investments ever since. But the move to ATSC 3.0 is not being forced by the government. Instead, the determining factor this time around will be money — many station owners will be calculating how long they can hold out until competition and consumer demand guarantee that the return will be worth the investment.

A few pioneers came out in support of ATSC 3.0 last week, as a broad-based group of station executives announced that they were planning a national roll-out of “next-gen TV service” by the end of 2020. “ATSC 3.0 offers new ways for local broadcasters to tell stories, interact with viewers, make an impact in our communities and innovate across screens and devices,” said Tegna President and CEO Dave Lougee in a prepared statement of support. “The new standard will allow for clear, UHD signals, personalized advertising and the potential for exciting new adjacencies such as smart city infrastructure and connected vehicles.”

That commitment was vague in some ways, but still important for the signal it sent. For example, it told consumer electronics manufacturers that if they release ATSC 3.0 capable TV sets in 2020, it won’t be a completely quixotic gesture. By that time, a reasonable number of early adopters in key markets should be able to take advantage of the features.

Of course, not every broadcaster is making the same promise. Hilton Howell, President and CEO of Gray Television, which claims to reach 10 percent of U.S. households via 103 stations, was not a signatory to the ATSC 3.0 agreement but insisted that his organization was fully prepared for the upgrade. “Gray tries to focus on being nimble and being profitable,” he said during a panel discussion at the TV 2020 conference held at NAB Show NY. “We are deploying ATSC 3.0- and 4K-capable technology. When 3.0 is ready, Gray is ready. Right now, the market has to catch up with the technology — but that is happening quickly. Gray is ready for 3.0, absolutely.”

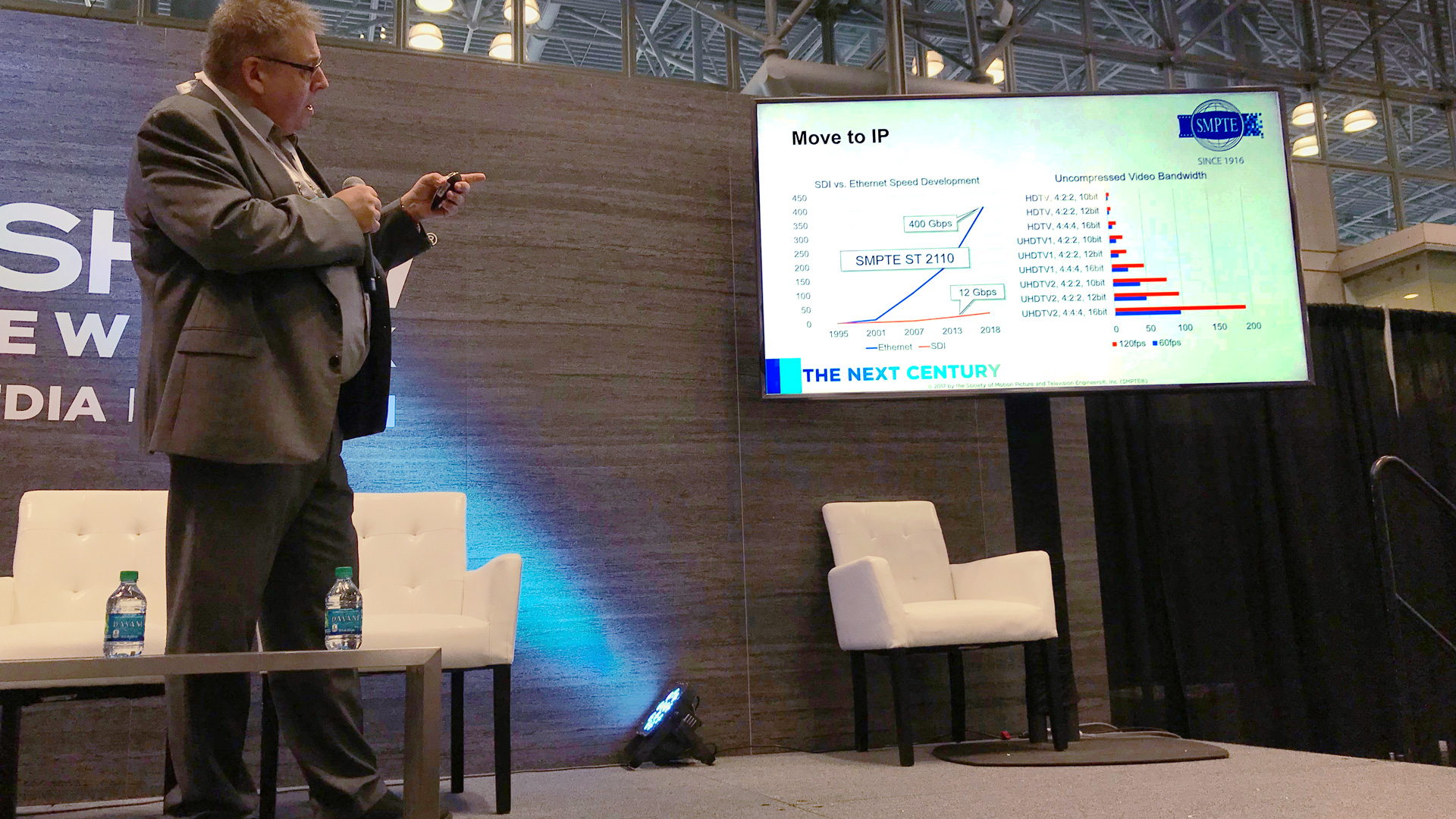

Gray Television may be ready for 3.0, but many others in the industry are still getting comfortable with all of the new buzzwords that come with it — terms like HDR, HFR, and WCG that describe the imaging improvements that come with new standards like SMPTE ST 2110, ITU-R BT.2020, and the like. At a well-attended presentation titled “The State of UHD and HDR: Five Things Everyone Should Know,” SMPTE Director of Standards Development Thomas Bause Mason offered a whirlwind 30-minute tour of key technical issues, referring attendees to a baffling array of standards and publications for more detailed information.

SMPTE Director of Standards Development Thomas Bause Mason runs the numbers when it comes to uncompressed video bandwidth.

Bryant Frazer

Mason noted some of the ways that UHD is pushing the boundaries of what’s physically possible in broadcast. For instance, he said researchers have suggested a minimum frame rate of 80fps for the best quality UHD2 (7680 × 4320) images, while the upcoming UHD2 broadcasts of the 2020 Olympics are scheduled to take place at 60fps. That is due to satellite bandwidth constraints, Mason said, suggesting that future UHD2 broadcasts will in fact run at 120fps once the bandwidth is available. And though wider color gamut is an oft-cited advantage of UHD vs HD, he noted that no consumer displays are yet capable of displaying the full Rec.2020 color space, with most reproducing the P3 gamut or slightly less.

And he offered a simple explanation of why the industry is becoming eager to make the IP transition, showing a chart that illustrated how SDI and Ethernet speeds, which tracked fairly closely through 2001, started to widely diverge in the 21st century. Today, SDI has reached a history-best 12 Gbps, while Ethernet is flirting with the 400 Gbps benchmark. That means that while 12G-SDI is adequate for HDR1 (3840 x 2160), only 100 Gigabit Ethernet has the speed required to carry uncompressed UHD2 signals. Combined with the cost-efficiency of off-the-shelf networking components, that makes IP infrastructure the safe bet for future-proofing any forward-looking broadcast facility.