How a Trove of Autobiographical Drawings from the Legendary Filmmaker Inspired a More Subjective and Personal Documentary Approach

Mark Cousins had been writing about film and presenting films on the BBC series Moviedrome when he made an international splash with the 15-hour documentary The Story of Film. It aired in the U.S. on TCM in 2013.

Jean-Luc Godard’s idea of conducting film criticism through the medium itself is a guiding principle through his work. A Story of Children and Film focuses on images of childhood. He has two works in progress: Dear John Grierson, which is about the history of documentaries, and Women Make Film.

But his most recent feature is The Eyes of Orson Welles. Welles is a contradictory figure, mythologized inaccurately as a director who peaked with his first film rather than a filmmaker whose interests extended far beyond the boundaries of conventional Hollywood work. He’s also been the subject of numerous biographies and documentaries, the most recent being Morgan Neville’s They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead.

The Eyes of Orson Welles finds a fresh angle, using Welles’ drawings as an entry point into his work. Addressing Welles in his voice-over, Cousins takes the director off his pedestal and brings a personal touch to The Eyes of Orson Welles.

Janus Films trailer for The Eyes of Orson Welles

StudioDaily: Were you deliberately trying to evoke Welles in your choice of camera angles and the way you film architecture?

Mark Cousins: For the most part, no. For the scenes in North Africa, I was putting the camera low like he did. But I’ve seen many films where filmmakers try to ape their subjects’ look, and it’s often a mistake. Most of my shots are longer-lens, eye-level and not using those famous foregrounds of Orson Welles. When I talked about him as the greatest filmmaker of looking upwards, I looked upwards.

When did you first learn about his work in drawing and visual art?

I knew a little bit. For many years, I had the book of his drawings he’d done for his daughter. I didn’t know about the extent of his work in it. I learned that he’d studied in the Art Institute of Chicago. I didn’t know he drew all the time. I didn’t know that he drew in an autobiographical way, like a visual memoir. Only when I met his daughter Beatrice did I think “Oh, there’s another angle on this. Not everything has been said.”

The voice-over is addressed to Welles. Why did you decide to do that?

A number of reasons. In a way, he is still alive. His work is very vibrant still. It hasn’t dated. I wanted to get away from the objective and historical voice we get in so many documentaries. I wanted to do something more subjective. When you write in the first person, you get into a more emotional character that I was interested in. I also filmed it because Orson Welles was a father figure to many of us with a passion for cinema. When my own father died, I gave a speech in the church where I stood up and said, “Dear Dad,” speaking to him directly. It kinda worked, at least for me. I thought it would work for my movie dad.

You have a number of tattoos of artists who’ve inspired you, like Abbas Kiarostami’s name in Farsi on your arm.

Yes, I worked with him in Italy and did some little trips to Iran.

Do you have a tattoo of Welles?

Yes, I do. When I first met his daughter, I hid it. I thought it might be embarrassing because some people think of tattoos as quite adolescent. Not me. It’s on my right arm. After we had two martinis, I turned to her and showed it. I was brought up Catholic, and the Catholic tradition has stigmata, where things are written on the body. A lot of the people who really inspired me are.

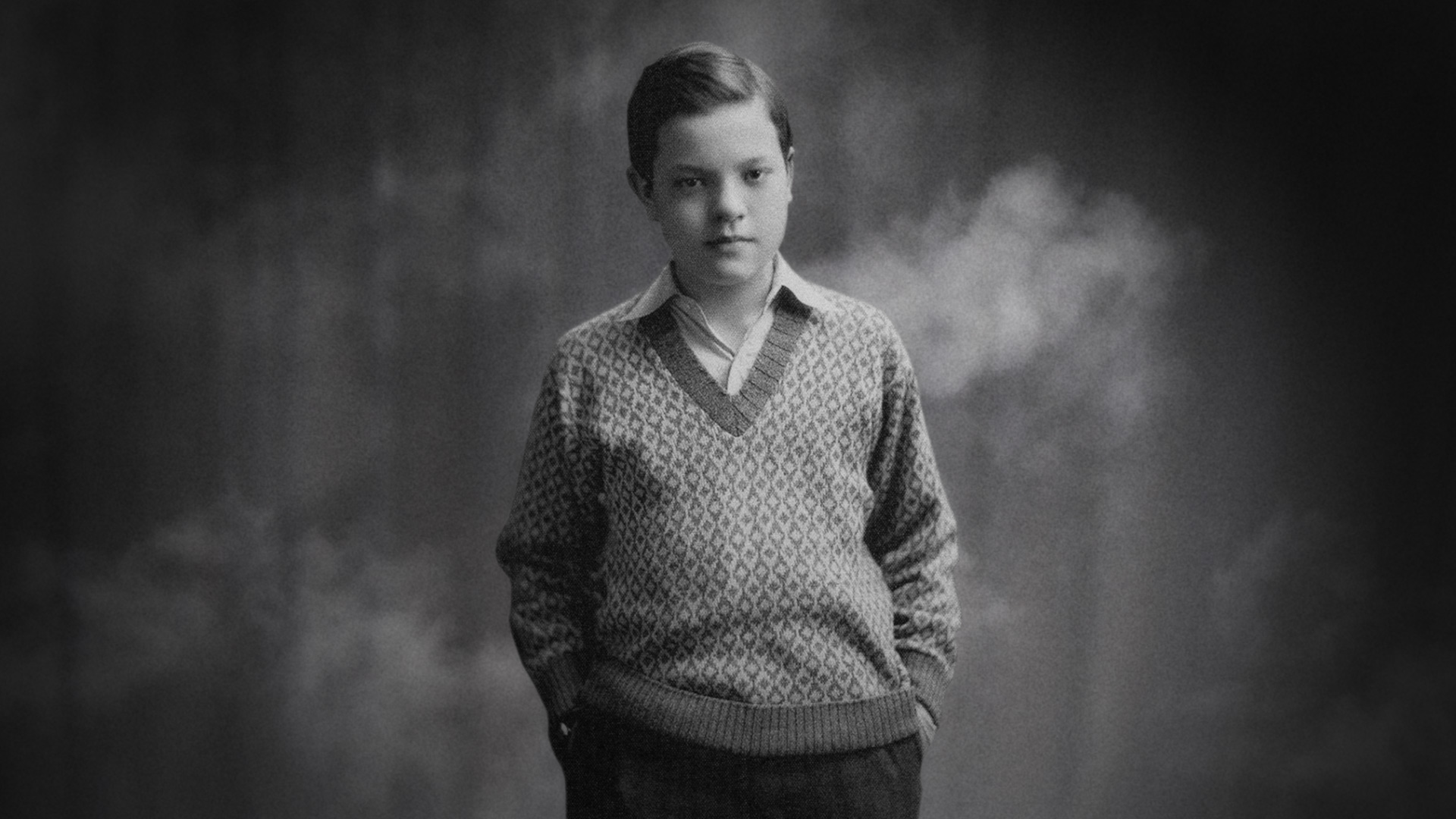

Orson Welles art

You find connections between Welles’ drawings and his films, which are sometimes obvious, like his sketches for The Trial. Sometimes, they’re less so, like the drawings of Irish people and his fondness for making himself up to look older. Thankfully, you don’t show any images of Rosebud, but were you influenced by that idea of the connection between past and present?

Welles thought a lot about that connection. Many of his films are set in the past. He felt passionately about it. He was really spoiled by his time in Spain and Morocco. I made this film before I saw The Other Side of the Wind [Welles’ final film, recently completed posthumously]. There are a lot of opinions about it, but mine is that it’s an Irish wake. By that, I mean that in Ireland when someone dies, we drink a lot, we talk and we celebrate. His last film has John Huston in it, and Huston was obsessed by Ireland. Those early experiences for Welles really helped form his imagination. Those sketches are revealing of what formed this young, vibrant mind.

Given that you’re Irish, were you particularly attracted to Welles because of his working in Irish theater as a young man and going on to cast Irish actors?

I wouldn’t say so. I would say I was attracted to his passion. In the film, I’d say that’s not only in Ireland, but in Spain, Italy and the Arab world. He was very taken by those parts of the world where people live a lot and are Dionysian. He had very little use for the Scandinavian world. We do have a lust for life in Ireland, and that’s one of the appeals of his work for me.

Orson Welles photographed in January,1950

Walter Carone/Paris Match via Getty Images

You repeatedly use the image of Welles, lying on a bed with his hand resting on his head, for punctuation. Why did you choose that particular one?

Well, it’s called The Eyes of Orson Welles, and I wanted a photo where his eyes are clear and prominent. The second reason is that most of us, if we have an image of Welles, it’s an old man with a grey beard. But he was most famous in his 20s and 30s. So I wanted to capture the vitality of the man. He’s young and handsome in that picture.

I find it very ironic that he’s become a legend to people who know nothing about film history. There are many people who’ve seen Citizen Kane but have only seen maybe five other films made before Star Wars. But if they saw Chimes At Midnight, much less F For Fake or The Other Side of the Wind, they’d hate them. Do you think your film can speak to those people?

It’s difficult, because Welles was an experimental artist. His work is not immediately accessible. Some of it is. I’d say that the first half of The Magnificent Ambersons is. He wanted to touch people, in a way that’s labyrinthine, complex and extremely tactile. He made these kind of dream-films. I’m always in the business of trying to introduce young people to cinema. I feel as though I’m a drug pusher, with the drug of cinema. So yes, there’s a big, beating heart to Orson Welles, despite the complexity of his style and themes. There’s a humanity and emotion at the center. He’s different from other very experimental filmmakers, like Jean-Luc Godard, who don’t have that core. So that’s why young people can get him, although I don’t think Citizen Kane is the best place to start with. It’s an old man’s film.

You used the DJI Osmo [gimbal-stabilized camera] on The Eyes of Orson Welles.

This is the first time I’ve used it. I’ve used other kinds of cameras before. I’ve worked with Christopher Doyle and used Arri cameras. I wanted it to be a personal journey, so I wanted the camera to feel like a phantom or ghost. I needed something small.

For your projects based on use of film clips, how do you research and organize the material?

I don’t have to do loads of research because I know the films well. In terms of getting material, I work with producers who find masters. I’m currently making a 15-hour film called Women Make Film. In each case, I radically reject computer screens. I make a log by paper and filing cards. In the Orson Welles film, I wrote each scene on a card. It’s much easier to shuffle cards and get them in a sequence that seems right than writing down on a structure on a computer screen. Many filmmakers use this technique, and I got it from someone who worked on Apocalypse Now and some of the Coppola films, who said, “Never touch a computer screen when you can work by hand.”

Has legal clearance ever been an issue regarding the clips you wanted?

Sometimes we clear them, often we don’t. When we don’t, we use fair use. In The Eyes of Orson Welles, the films are being commented on in a specific clip. It conforms precisely to the fair use principle.

I’m sure you must get asked in every interview about being a man making an epic-length film about female directors.

There’s a revolution happening in the film world, a movement, a popular front. Some of the best films on this subject are by women, like the Alice Guy-Blaché and Jane Fonda documentaries that came out last year. I’m part of this movement. All movements for change should have a range of people working in them, including men. Tilda Swinton is the executive producer. She and Fonda are doing the voiceover. Swinton is one of the most credible women in the industry. I know an awful lot about the history of woman directors. I’m talking about Japan in the 1950s, Korea in the 1960s, Iran in the 1970s, Albania in the 1970s, etc. This knowledge is very useful.

In The Story Of Film, there was an effort to revise the canon towards something less centered around North America and Europe. There have been a number of recent efforts to do away with auteurism and old notions of cinephilia in favor of something that puts films by women and/or people of color at the center. How do you feel making a documentary about Orson Welles fits into that climate?

When I was making The Story Of Film, I wasn’t trying to over-assert the greatness of African directors or female directors or Iranian directors. I was just trying to level the playing field a little bit in a spirit of fairness, so that the great directors of West Africa could have their say. We don’t want to over-praise people, but nor do we want to under-praise them. We want to go for balanced evaluations. Wanda is a very good film, but the great female directors in history are also in Japan, Korea and West Africa. We have to make these judgments and avoid what I call the fisheye lens that distorts our own experience and perception. The whole of film history has been told through a fisheye lens.

One issue is that, even living in New York, I’m not sure how to see any Albanian films, much less Albanian films made by women in the ’70s.

Go on YouTube. I’m lucky enough to have been involved in the Albanian film archive, and they have been subtitling, restoring and making those films available. When I was young, it took me 10 years between hearing about Citizen Kane and seeing it. That’s not the problem anymore. It’s not that hard to see the films of Moufida Tlatli from Tunisia or Kinuyo Tanaka from Japan, etc. Some of these films are a click away. The problem is: what five words do I type into the search engine. It surprises me that people don’t type “Japanese female directors from the 1960s.” Type that, get some information. It’s a question of curiosity, I think.

Orson Welles art

In discussing Orson Welles around the figures of the jester and the king, how much do you think his fascination had to do with his politics and his ambitions as an artist?

He was bigger than life. You can approach him through these chess-piece types, these archetypes. I think they relate to both his politics and ambition. His politics were brave and remarkable, which sends us in the direction of the questions about equal rights. Orson Welles’ imagination was formed in the 1930s and 1940s, when the big figures were Hitler and Mussolini. They were epic, dangerous human beings. It’s no surprise that he made epic, dangerous characters like Gregory Arkadin and Charles Foster Kane. The structure I used from my film came naturally from the work.

Did you start out with the structure planned out?

The structure came first. I’d known Orson Welles’ work well, so I knew there was something epic and archetypal about it. That quote from Walt Whitman at the end: “I’m large, I contain multitudes.” I had a meaty and substantial structure and then had the freedom to explore. The idea came to me in less than five minutes of taking to Welles’ daughter.

Looking at your filmography, it seems bookended by The Story of Film and Woman Making Film, but you’ve been quite prolific, making eight films in between. What are the differing demands of projects that big versus The Eyes of Orson Welles?

I think the demands are creative ones. If you make a film about Orson Welles, how do you avoid banality, the clichés and received opinions about him? On a really big scale, like 16 hours, it’s a question of confidence. Can this sustain itself? Is this story strong enough? Overall, I don’t think there’s much difference between making an 18-minute documentary or fiction film, which I’ve done, and a longform one. Even if people can shut off TV immediately and have to go and seek out a film in the theater, I believe they still want something enriching and layered. If you believe in that, it doesn’t matter how long it is.

Director Orson Welles on the set of Citizen Kane (1941).

RKO Radio Pictures/Photofest

Orson Welles obviously had a very personal vision. As I was saying earlier, one aspect of the #metoo movement has been challenging the idea of a white male genius as a single guiding vision behind cinema and rejecting auteurism has been part of it. Do you consider yourself an auteurist?

Until she died last year, for me the greatest living auteur was Kira Muratova. One of the greatest auteurs alive now is Agnes Varda. There’s nothing male about the idea of the auteur. I work with a lot of colleagues in collaboration. I’m in a project now that I can’t name that feels like a committee. Someone had to say, “Here’s the horizon, here’s the direction, here’s where we’re headed,” and I said it. Is that being an auteur? When I go to the cinema, and I go to the cinema most days, I want to see a personal vision. If that’s auteurism, absolutely. When I saw Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, I thought it was one of the strongest visions I’d seen in years, although several people directed it. That’s what I want, not just from cinema, but art in general: someone to lead me and take me by the hand.

The Eyes of Orson Welles opens today at the IFC Center in New York City and on March 29 at The Roxie in San Francisco.

Did you enjoy this article? Sign up to receive the StudioDaily Fix eletter containing the latest stories, including news, videos, interviews, reviews and more.